Brian Grim (葛百彦), Ph.D.

I delivered a keynote speech at the Oct. 13-14 conference at Minzu University in Beijing on religion’s role in China’s Belt and Road initiative using data from my research at Boston University. Below is a summary of my presentation.

Chinese President Xi Jinping launched the Belt & Road Initiative in 2013. Over the past five years, scores of countries and international organizations have actively participated in the initiative which, according to Chinese authorities, promotes common development and sharing, policy communication, facility connectivity, unimpeded trade, financing, and people-to-people links.

As with any grand plan, challenges are numerous. Just as the pilgrims in the Chinese epic Journey to the West had to overcome a series of challenges to bring Buddhist scriptures back from India, Chinese goods, services and businesses also need to overcome many challenges on the road to success. One leading Hong Kong Business CEO investing heavily into the Belt and Road Initiative pointed to cultural barriers as “quite the most challenging part” of being successful.

In the introduction of my presentation, I shared own personal history in China, beginning in 1982 when my wife and I taught English at Hua Qiao University in Fujian, almost two decades before Xi Jinping was governor of the province. During that year, our oldest daughter (葛天恩) was, we are told, the first American to be born in China after China and the U.S. normalized relations during Pres. Jimmy Carter’s administration. In those years having an electric fan was considered a luxury, and we were the only private individuals we knew with a camera. How much has changes since then! Today, there are about 1.3 billion active mobile devices in China, most with a built-in camera.

I also shared about my work from 1985-88 in China’s northwest Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, where I worked with the former governor, Wang En-mao, a Long March colleague of Mao Zedeng and Deng Xioping, on several initiatives to empower Uygurs educationally and economically. During those years, a proposal I worked on for a trilingual graduate school — Uygur, Putonghua (Mandarin) and English — eventually was approved personally by then Chinese Premier Deng Xioping. The school was unfortunately never established.

One highlight of that period was a trilingual concert in Uygur, Putonghua and English at Xinjiang’s newly constructed Great Hall. As part the educational exchanges involving more than 1,000 students and teachers in Xinjiang that I was organizing between U.S. Baptist universities and universities in Xinjiang, a choir of students and young teachers from our summer program performed a song popularized by American Singer, Sandi Patty, “Love in Any Language.”

- Love in any language, straight from the heart

- Pulls us all together, never apart

- And once we learn to speak it, all the world will hear

- Love in any language, fluently spoken here.

In my 2018 keynote speech, I argued that such experiences from years ago indicate that the possibilities of interfaith and intercultural understanding in Xinjiang are real, and such types of programs need to be revisited.

Religious Diversity: An Aid to China’s Economy

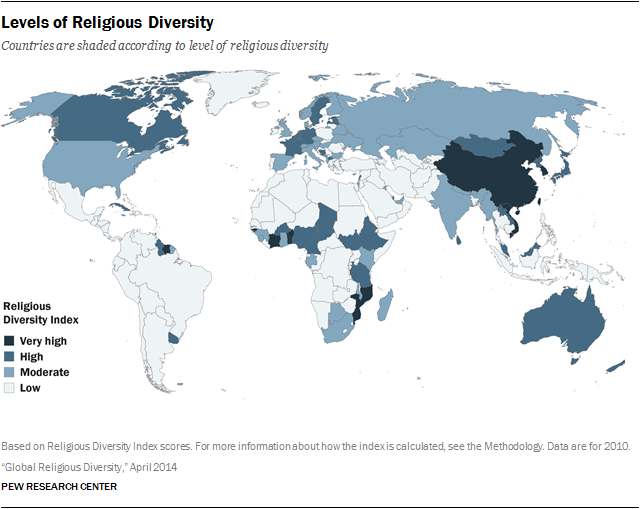

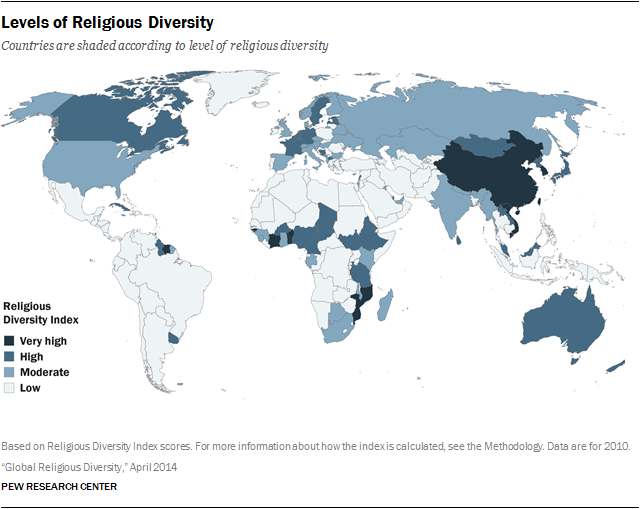

A Pew Research Center religious diversity study – based on methodology I developed with Todd Johnson – finds that about one-in-three people live in countries with high religious diversity (also see Chapter 3 in our book, The World’s Religions in Figures).

While the majority of the world’s countries (59%) have relatively low religious diversity, because many countries with low diversity have small populations, only a third (33%) of the world’s people live in them according to the study. About a third (32%) of the world’s people live in countries with moderate religious diversity and another third (35%) live in countries with high or very high religious diversity.

China has a very diverse mixture of the eight major religious groups counted in the Pew study: Buddhists (18.2%), Christians (5.1%), unaffiliated (52.2%), Muslims (1.8%), other religions (0.7%), Hindus (<1%), folk religionists (21.9%) and Jews (<1%).

During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, religion was completely outlawed and people were routinely beaten and killed for having superstitious or religious beliefs. While it is true that today China has very high government restrictions on religion relative to other countries in the world, current conditions are far less restrictive than they were in the 1960s and 1970s.

Today, China has the world’s largest Buddhist population, largest folk religionist population, largest Taoist population, 9th largest Christian population and 17th largest Muslim population – ranking between Yemen and Saudi Arabia (Pew Research Center 2012).

Acknowledging China’s very high religious diversity is important because countries with higher levels of religious diversity are more globally competitive. Elsewhere (Grim 2015) I have made the case that China’s very high religious diversity contributes to the country’s remarkable economic growth, which has not only fueled global growth but also lifted more than 500 million people out of abject poverty.

Globally, what do the data say about the relationship between religious diversity and global competitiveness? We can see clearly that countries with higher levels of religious diversity are on average significantly more globally competitive by comparing the Religious Diversity Index (RDI) scores of the top 27 economies on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) with the 110 lower ranking economies (China is ranked 27th), as shown in the table below. The median RDI for the top 27 economies is 5.4 compared with a median of 2.5 for the remaining 110 economies for which the World Economic Forum calculates a GDI score. Looked at another way, 59% of the top economies (16 of 27) have high or very high religious diversity compared with just 17% of the remaining 110 economies (19 of 110).

Globally, what do the data say about the relationship between religious diversity and global competitiveness? We can see clearly that countries with higher levels of religious diversity are on average significantly more globally competitive by comparing the Religious Diversity Index (RDI) scores of the top 27 economies on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) with the 110 lower ranking economies (China is ranked 27th), as shown in the table below. The median RDI for the top 27 economies is 5.4 compared with a median of 2.5 for the remaining 110 economies for which the World Economic Forum calculates a GDI score. Looked at another way, 59% of the top economies (16 of 27) have high or very high religious diversity compared with just 17% of the remaining 110 economies (19 of 110).

What are the mechanisms through which religious diversity contributes to economic competitiveness? First, research shows that diversity is in many situations a plus for businesses. And because more than eight-in-ten people in the world practice a religion, religious diversity is one of the most basic ways to increase what is called 2-D diversity, that is two dimensions of diversity, covering inherent traits (such as gender and age) and acquired traits (such as skills and education). Writing in the Harvard Business Review, Hewlett, Marshall and Sherbin (2013) note that “firms with 2-D diversity are 45% likelier to report a growth in market share over the previous year and 70% likelier to report that the firm captured a new market.”

Religion is a unique contribution to organizational and business diversity in that it can involve both inherent and acquired traits. That is, to the degree that someone follows the faith of their parents and/or community, it is inherent. And, to the degree that religion is a matter of personal preference and choice, it is also acquired through religious education and practice.

Second, diversity enhances creativity and is a critical component of building teams or organizations capable of innovating. Diversity stimulates the search for novel information and perspectives, leading to better decision making and problem solving. “Diversity can improve the bottom line of companies and lead to unfettered discoveries and breakthrough innovations. … Being around people who are different from us makes us more creative, more diligent and harder-working” (Phillips 2014).

Religious diversity within a country makes the local marketplace of ideas, products and businesses more diverse and innovative. Indeed, business and technological innovations often come from religious and other minorities who often have different life experiences and frames of reference from the majority population. In a sense, because they are a minority, they often have to try harder. As an example, some of the most successful global companies had leadership from religious minorities, such as Marriott International, which was founded and for many years led by a family who are devout members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), who number only 16 million worldwide. One of India’s most successful and respected companies is the Tata Group. It was founded and is owned by the Tata family who are members of a very small religious group called Parsis, a small subgroup of Zoroastrianism with fewer than 60,000 members.

And in China religious minorities add significant value to the economy, such as China’s domestic halal market valued at $20 billion annually (Allen-Ebrahimian 2016). And according to a study in the China Economic Review by Qunyong Wang (Institute of Statistics and Econometrics, Nankai University, Tianjin) and Xinyu Lin (Renmin University of China, Beijing), Chinese Christianity – another of China’s minority religions – boosts the country’s economic growth. Specifically, they find that robust economic growth occurs in areas of China where Christian congregations and institutions are prevalent (Wang and Lin 2014).

This also points to the possibility that China can benefit from this internal religious diversity by Chinese religious minorities playing a critical role in helping to successfully deal with businesses from countries and communities that share their background. For instance, even though China produces halal food for export, China’s halal industry remains a negligible 0.1 percent of a world halal market that’s “valued at more than $650 billion and is projected to reach up to $1.6 trillion within a few years. Huge growth is expected over the next several decades as the world’s Muslim population grows faster than every other major religious demographic, and as urbanization and rising incomes in developing countries with large Muslim populations mean that more of the world’s Muslims will be buying, rather than producing, their own food” (Allen-Ebrahimian 2016). Having Chinese Muslims become leaders for halal exports might help win the trust of Muslim populations around the world.

References

- – Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany (2016). “China Wants to Feed the World’s 1.6 Billion Muslims.” Foreign Policy. May 2, 2016.

- – Grim, Brian J. (2015). “The Modern Chinese Secret to Sustainable Growth: Teligious Freedom and Diversity,” The Review of Faith & International Affairs Volume 13, Issue 2, 2015.

- – Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Melinda Marshall and Laura Sherbin. (2013). “How Diversity Can Drive Innovation.” Harvard Business Review, December 2013. Internet:

- – Pew research Center (2012). The Global Religious Landscape

- – Phillips, Katherine W. “How Diversity Makes Us Smarter.” Scientific American, October 1, 2014.

- – Wang, Qunyong, and Xinyu Lin. 2014. “Does Religious Beliefs Affect Economic Growth? Evidence from Provincial-level Panel Data in China.” China Economic Review 31: 277–287.

More Photos

Launching Leaders Rolls Out Personal Development and Leadership Course to United Religions Initiative Cooperation Circles in Africa

Launching Leaders Rolls Out Personal Development and Leadership Course to United Religions Initiative Cooperation Circles in Africa The interfaith Launching Leaders course, offered by Launching Leaders Worldwide, Inc., is a cornerstone of the Empowerment Plus program at Religious Freedom & Business Foundation (RFBF). RFBF, Launching Leaders and URI have formed a partnership to work together to bring the powerful course initially to young people in Africa. URI is the largest grassroots interfaith peacebuilding network in the world.

The interfaith Launching Leaders course, offered by Launching Leaders Worldwide, Inc., is a cornerstone of the Empowerment Plus program at Religious Freedom & Business Foundation (RFBF). RFBF, Launching Leaders and URI have formed a partnership to work together to bring the powerful course initially to young people in Africa. URI is the largest grassroots interfaith peacebuilding network in the world.

Fernán de Elizalde, an Argentinian businessman and member of the Christian Association of Business Executives (

Fernán de Elizalde, an Argentinian businessman and member of the Christian Association of Business Executives (