By Brian Grim, RFBF President

By Brian Grim, RFBF President

The Wall Street Journal is not the place one might expect to find an essay titled What We’ve Lost in Rejecting the Sabbath, but that is what’s featured in today’s weekend edition. It’s even highlighted on the front page of the print edition. In the essay, Sohrab Ahmari looks back in U.S. history to a time when setting aside one day a week for rest and prayer was not only an American tradition, but one backed up with the force of law.

Across the U.S., Blue Laws used to mandate that businesses close on Sunday, the Sabbath in most Christian traditions. Even today in Europe, some countries continue to limit or prohibit shops from opening in Sundays.

Across the U.S., Blue Laws used to mandate that businesses close on Sunday, the Sabbath in most Christian traditions. Even today in Europe, some countries continue to limit or prohibit shops from opening in Sundays.

Ahmari argues that in an age of constant activity and smart devices blurring the space between home and work, we need it more than ever. Drawing on the thinking of the famouus rabbi and theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907–1972), Ahmari proposes that the Sabbath was a revolution, and in fact could be revolutionary today if more widely practiced.

It is difficult to imagine just how revolutionary the Sabbath vision must have appeared in the ancient world, where vast multitudes of people were slaves. Into such a world, there appeared a religion that told slaves they had an identity separate from their labor, that their nonwork was sacred. Judaism taught men and women to find inner liberty by freeing themselves from “domination of things as well as from domination of people,” as Heschel observed.

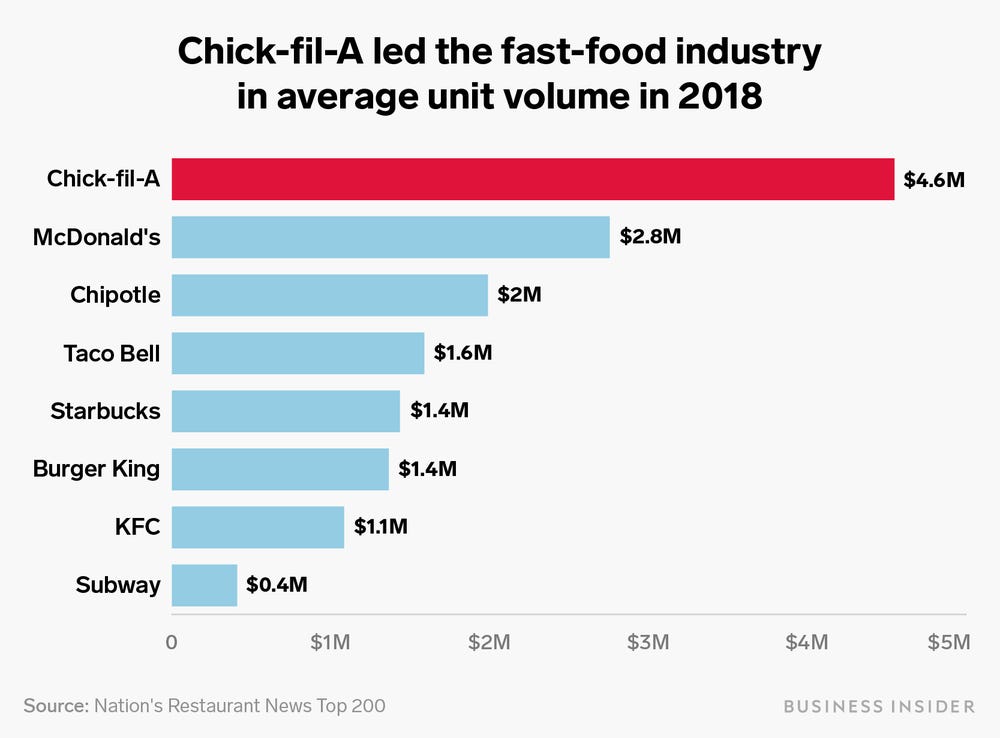

In practice, companies that close for the Sabbath in America today are doing quite well. For example, Chick-fil-A closes all its restaurants on Sundays, which seems to only increase demand. It regularly has the highest volume in sales (average unit volume) per location.

King Husein, CEO of Span Construction (the largest steel metal construction company in the U.S. and builder of Costco stores) also has a policy of no work for all in his company on the Sabbath. He believes that it’s core to what has made his company successful. See short discussion below, or full discussion here.

Of course, Sabbaths are different for different faiths, which not only makes policy around this topic difficult, but also presents difficulties for those whose Sabbath is not on Sunday, which includes Jews, Muslims and Seventh Day Adventists, to name a few. And, for those with a deeply held belief to maintain Sabbath observance, recent law has not always sided with the employee seeking an accommodation.

For example, as summarized by Beckett, “Darrell Patterson, a Seventh-day Adventist and longtime dedicated Walgreens employee, had a long-standing agreement with his supervisor at Walgreens—because he could not work on Saturday, the Adventist Sabbath, others would cover any shifts that occurred during that time.

“But when Walgreens executives scheduled an emergency weekend training after violating Alabama pharmacy law, Patterson paid the price for their error. Patterson was suddenly fired after he was unable to report to work on a Saturday. Forced to choose between his faith and providing for his family, Mr. Patterson sued Walgreens for religious discrimination, but both the district and appeals courts sided with the company.

“In 2018, Mr. Patterson appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Becket asked the Court to protect Mr. Patterson and the right of Americans of all faiths to live and work according to one’s religious beliefs, which includes a longstanding practice central to many faiths: observance of the Sabbath.

“The Supreme Court denied review in Patterson v. Walgreens on February 24, 2020.”

Patterson v. Walgreens from Religious Freedom & Business Fnd on Vimeo.

However, more and more companies are adopting an accommodation mindset when it comes to such issues. Google, for example, has recently launched a global employee resource group for Googlers of faith and their allies. One if its priorities is to help the company recognize and adjust scheduling so that religious employees’ holy days are respected and accommodated. See more here.