Brian Grim, President, Religious Freedom & Business Foundation

— Prepared Comments for Religious Diversity & Inclusion event at Texas Instruments HQ, May 6, 2019

Many people haven’t thought much about the connection between religious freedom and business, but I’ve been thinking about it at least since 1982 when my wife and I worked in the ancient port city of Quanzhou, home to one of China’s oldest mosques built by Muslim business people who first introduced Islam to China more than a thousand years ago. In the 1980s we also worked in Xinjiang, China’s far west, where Nestorian traders first brought Christianity to China along the old Silk Road nearly 1400 years ago.

Then in 1991 working right across the border in what is now Kazakhstan, the USSR was dissolved – in my office building, incidentally – first request of new President was for my faith-based NGO to help them turn the former Communist Party training school into the region’s first western-style business school, KIMEP. At the start of a new country, he saw the connections between faith, freedom and the economy.

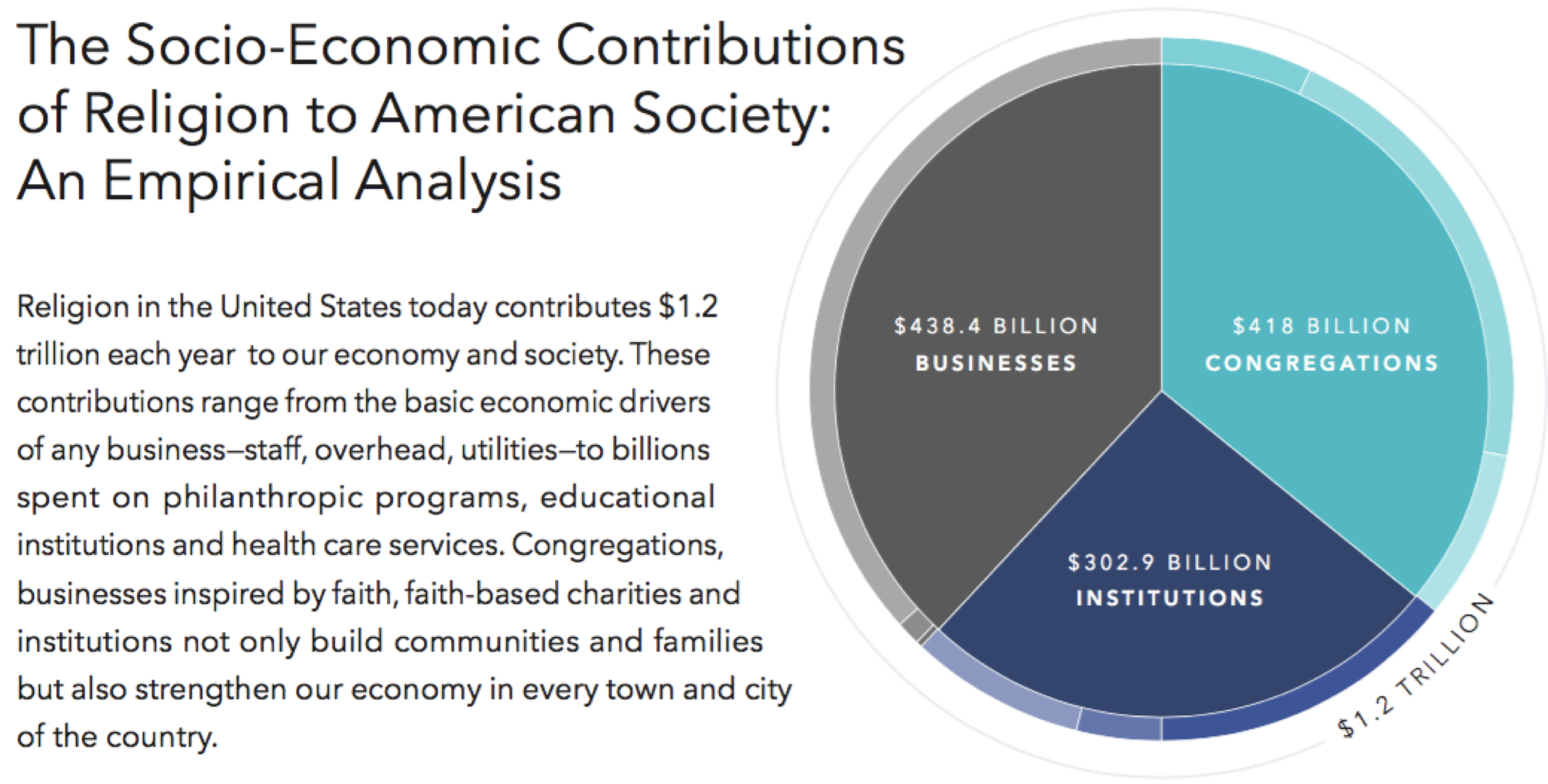

More recently I completed a study on the economic impact of religion set free by the freedom found in the United States.

So you could say there’s a lot of spiritual fuel being pumped unto the economy

So you could say there’s a lot of spiritual fuel being pumped unto the economy

My current work focuses on highlighting how religious diversity & inclusion – or workplace religious freedom – is an asset to the bottom line.

This work includes the privilege of working with some top experts, like Kent Johnson, who was Senior Council here at Texas Instruments for many years, as well as the Religious Freedom Center of the Freedom Forum Institute in Washington DC.

In this task, religious literacy is important. But I’m not talking about knowledge of religious beliefs and practices. It’s knowledge about how religion impacts the workplace and the marketplace –our coworkers and partners as well as our customers and clients.

Data can help us with this. First, religion is not in decline.

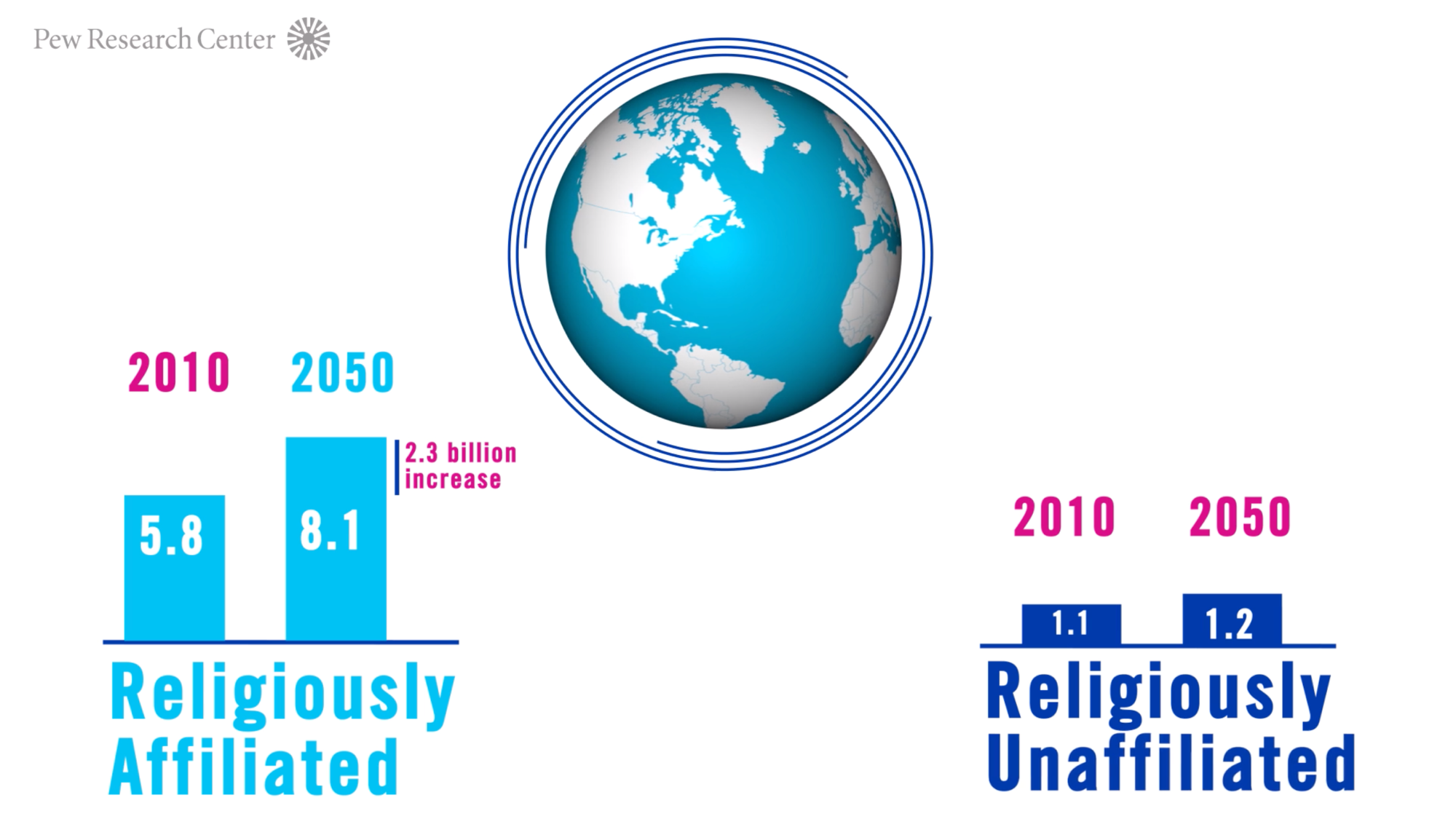

When I led the international data project at the Pew Research Center from 2008-2014, we projected that our planet will have 2.3 billion more religiously affiliated people by 2050 compared with just 0.1 billion more religiously unaffiliated people.

When I led the international data project at the Pew Research Center from 2008-2014, we projected that our planet will have 2.3 billion more religiously affiliated people by 2050 compared with just 0.1 billion more religiously unaffiliated people.

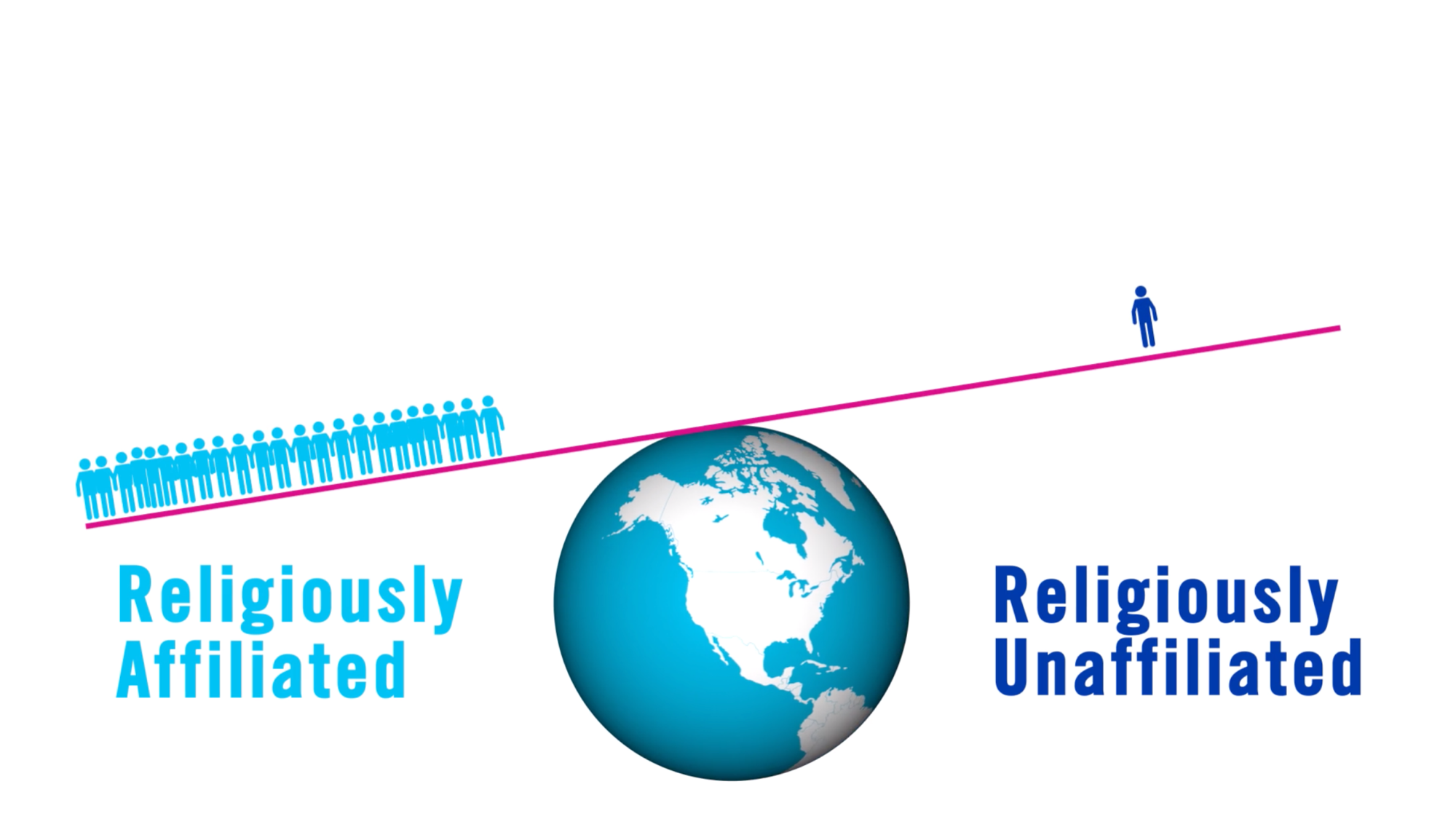

That’s like religion “winning” 23-to-1.

That’s like religion “winning” 23-to-1.

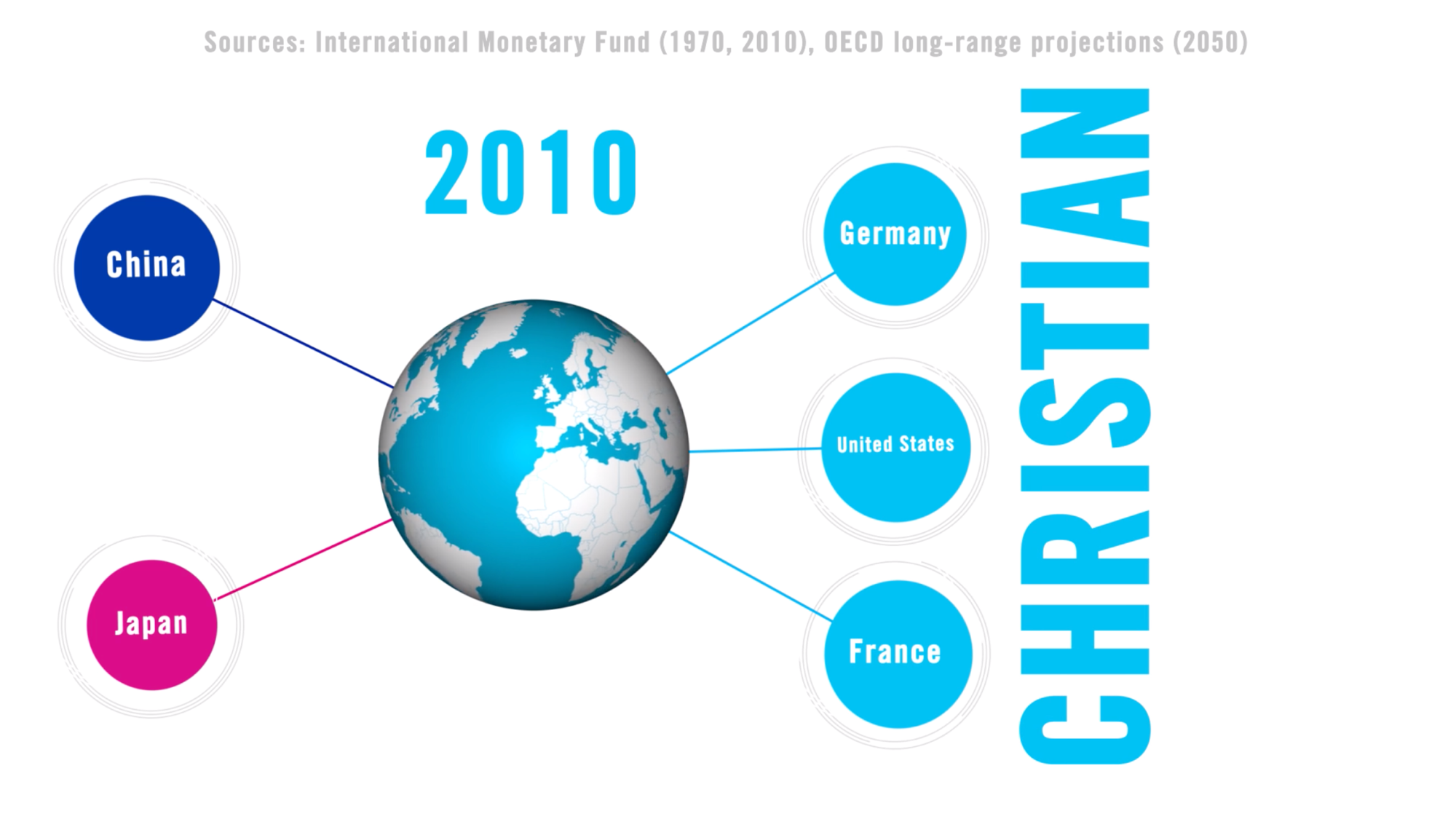

This religious growth is changing the global marketplace. Today, three of the top five economies are Christian-majority.

This religious growth is changing the global marketplace. Today, three of the top five economies are Christian-majority.

But in 40 years, only one is projected to be. The other four top economies in 2050 will include countries where Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists and the unaffiliated predominate.

Research shows that this religious growth can be good for the workplace and the bottom lines of businesses – as long as restrictions on freedom of religion or belief are kept low.

Research shows that this religious growth can be good for the workplace and the bottom lines of businesses – as long as restrictions on freedom of religion or belief are kept low.

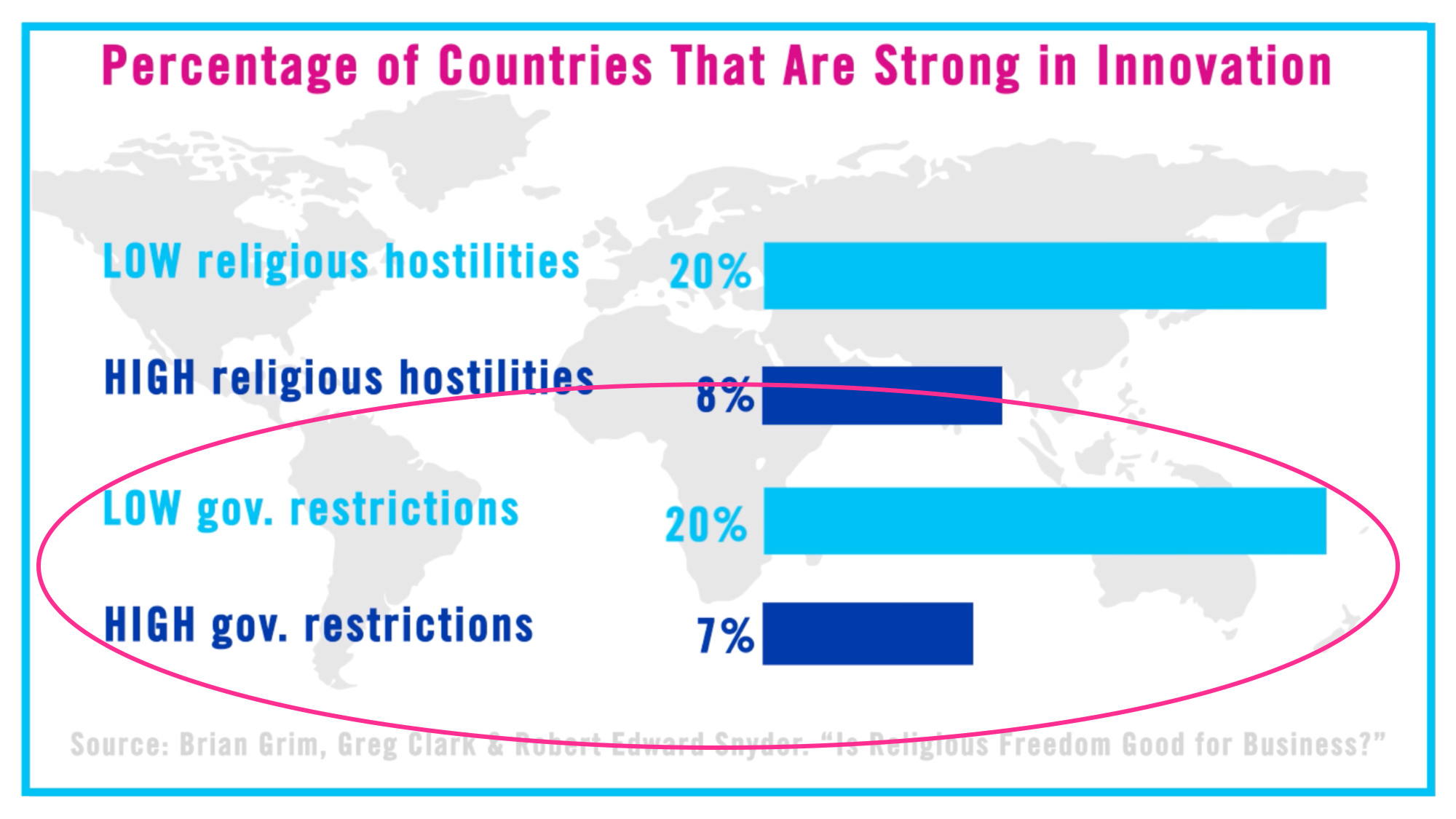

In such countries, innovative strength is more than twice as high as in countries where governments and societies don’t respect freedom of religion or belief. So, freedom to believe – or not believe – is good for business, as I’ll come back to in a moment.

But the data on respect for freedom of religion or belief in the U.S. and worldwide are very concerning.

Annual studies that I initiated while at the Pew Research Center find that restrictions on religion and belief are high or very high in 40% of countries.

Annual studies that I initiated while at the Pew Research Center find that restrictions on religion and belief are high or very high in 40% of countries.

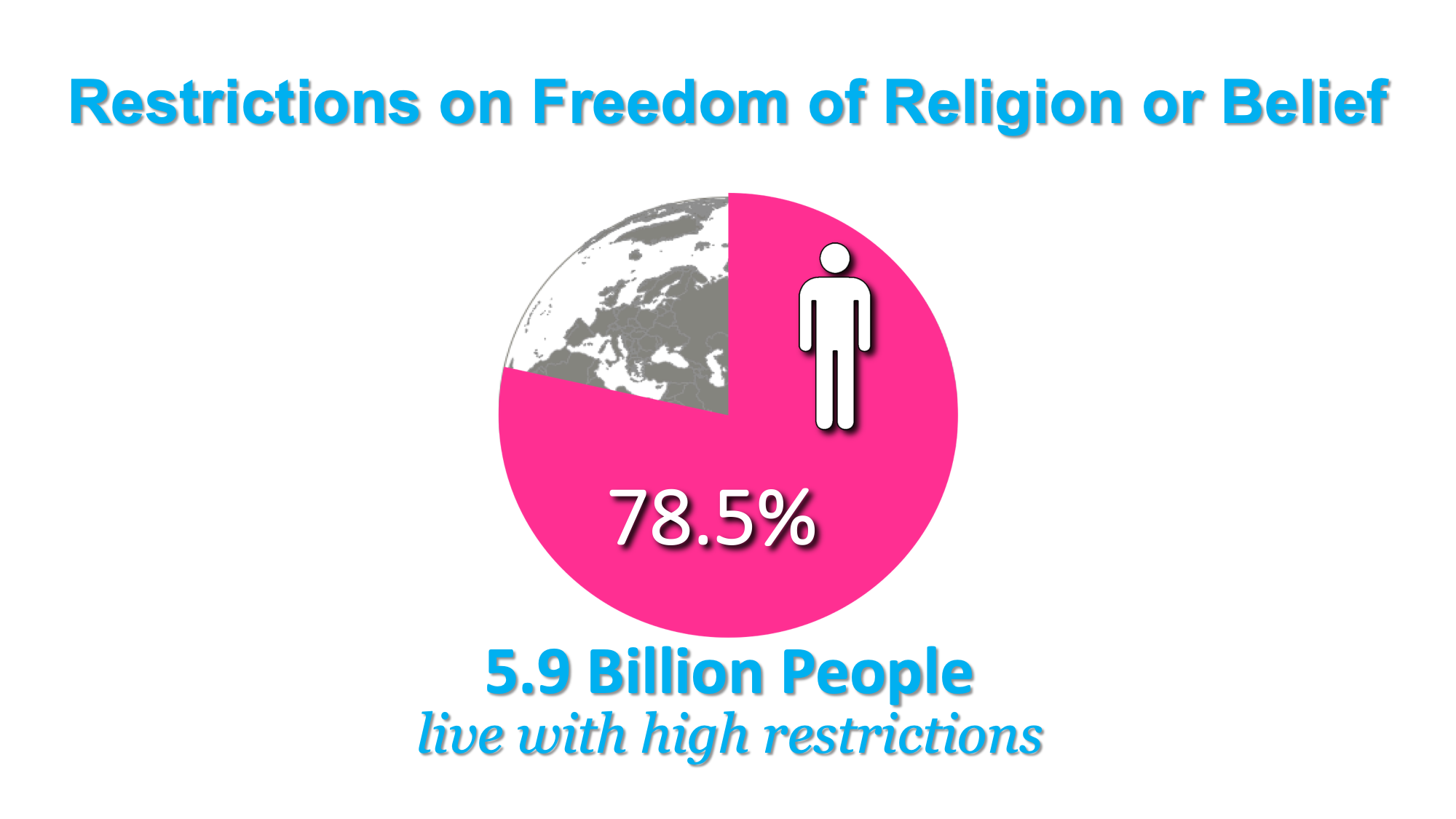

But because some of these countries (like China) are very populous, some 5.9 billion people (nearly 80% of the world’s population) live in countries with a high or very high level of restrictions on religion.

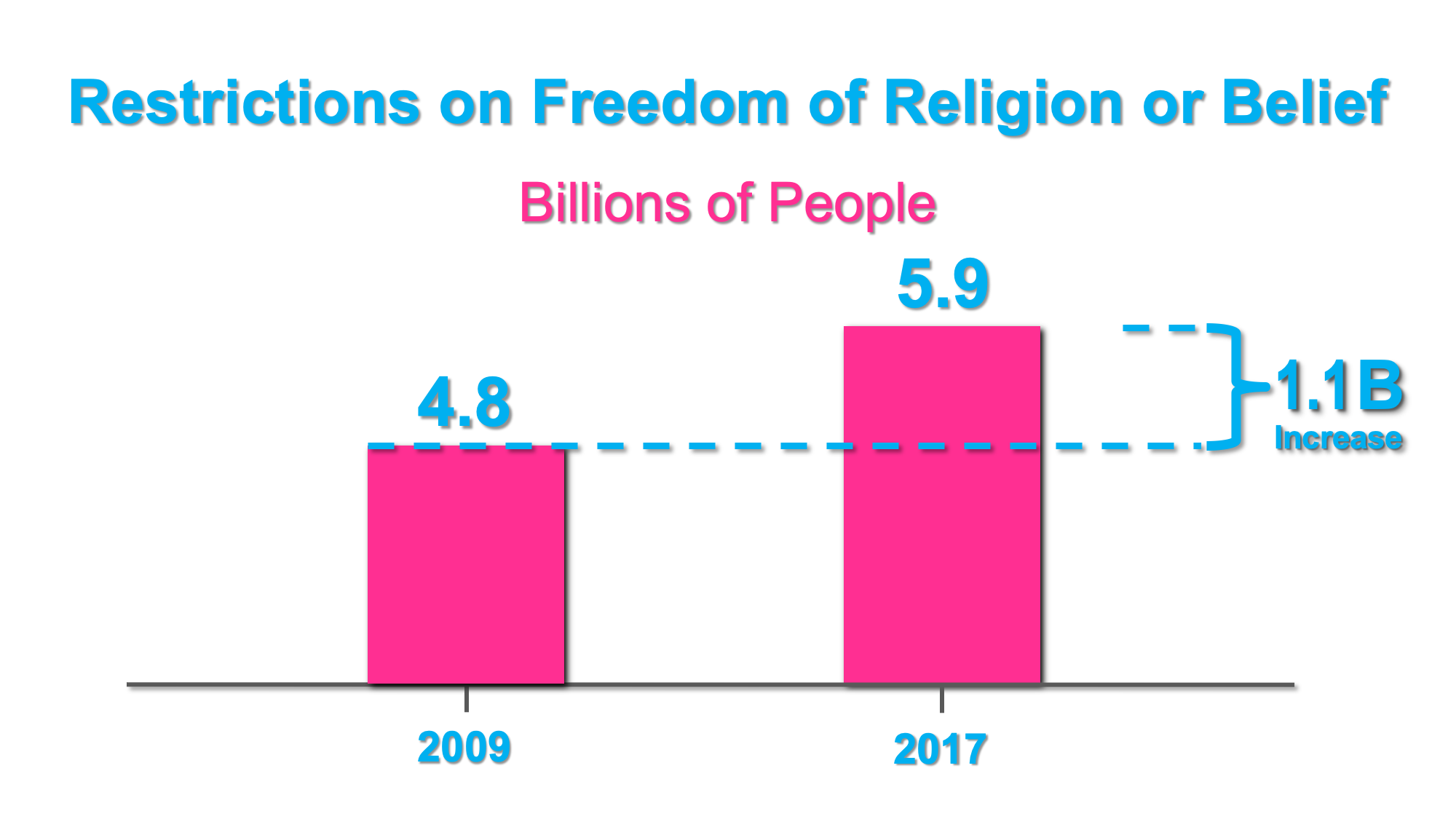

Since 2009, the number of people living in countries with high religious restrictions and hostilities has increased from 4.8 to 5.9 billion people – that’s an increase of 1.1 billion more people living in countries where freedom of religion or belief is under duress, based on studies from the Pew Research Center.

Since 2009, the number of people living in countries with high religious restrictions and hostilities has increased from 4.8 to 5.9 billion people – that’s an increase of 1.1 billion more people living in countries where freedom of religion or belief is under duress, based on studies from the Pew Research Center.

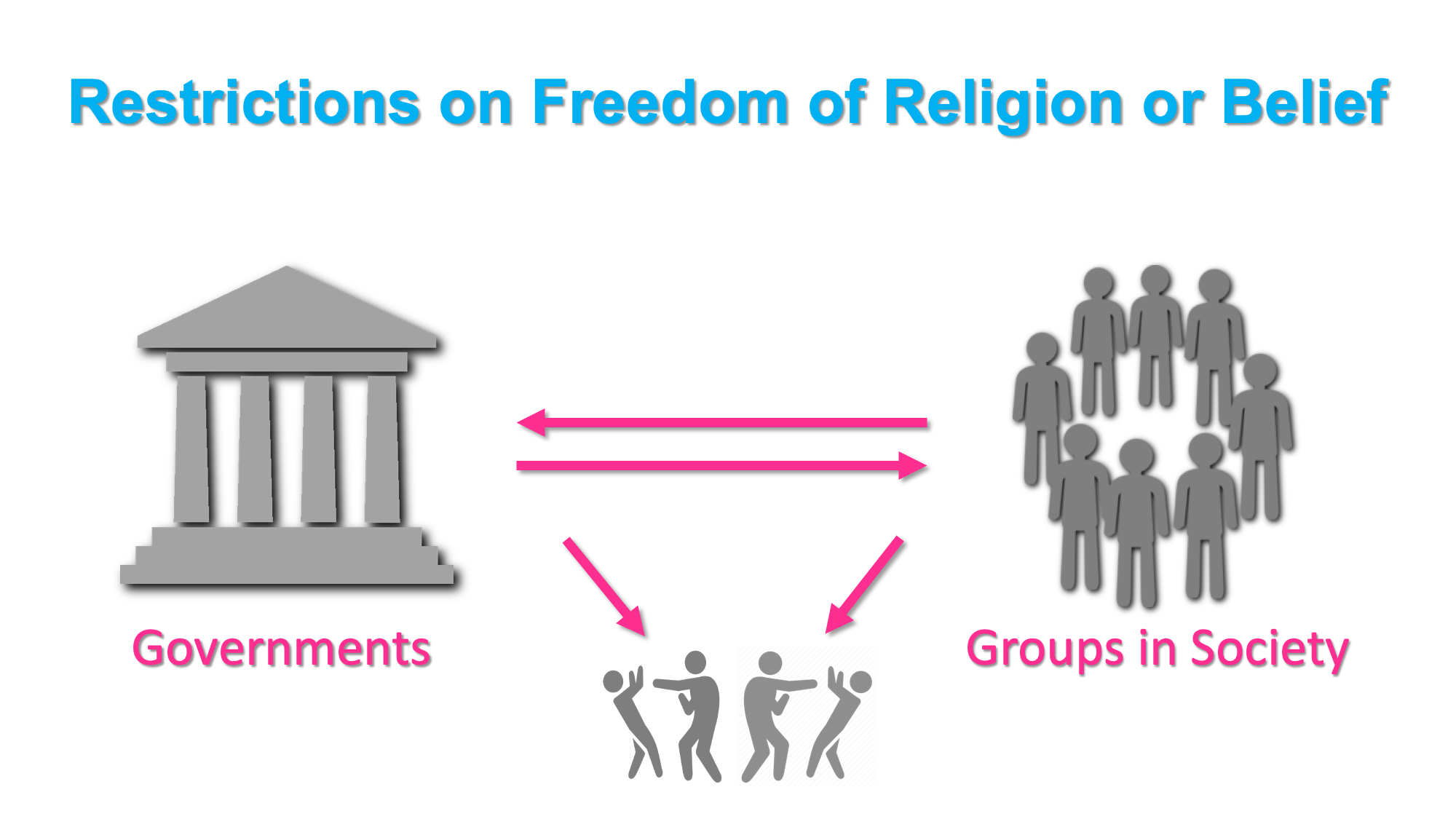

The restrictions come from two main sources: the actions and policies of governments, and the social hostilities involving religion coming from people and groups in societies.

The restrictions come from two main sources: the actions and policies of governments, and the social hostilities involving religion coming from people and groups in societies.

So, what are examples of social hostilities involving religion?

These include attacks on places of worship, such as the recent murders in a California synagogue and last fall’s massacre in at Pittsburg synagogue.

Social hostilities involving religion include the recent Easter Sunday bombings of churches in Sri Lanka that lefty hundreds dead and as many or more injured. They also include the recent Friday prayer massacres in two New Zealand mosques.

Social hostilities involving religion include the recent Easter Sunday bombings of churches in Sri Lanka that lefty hundreds dead and as many or more injured. They also include the recent Friday prayer massacres in two New Zealand mosques.

Such hostilities also include attacks motivated by religious hatred to people with no religious beliefs, such as Alexander Aan, an Indonesian who was beaten by a mop for declaring himself and Atheist, and then jailed by police for two years because in Indonesia blasphemy is a crime.

This case shows the frequent close connection between religiously biased laws and social hostilities involving religion.

Now let’s turn to examples government restrictions on freedom of religion or belief.

I’ll give some examples from China, because some of the same policy perspectives it has on religion are paralleled in some of its economic and security policies.

China has been on a several year campaign to not only remove crosses from churches and Christians from churches, but also church buildings from existence, such as the recent demolition of a church in Wenzhou, seen in these 24-hour before-and-after photos.

In China’s far west, up to one million mostly Uygur Muslims have been forced into re-education camps in the government’s attempt to stamp out the possibility of Islamic radicalization.

Two of my four kids were born in this region back in the 1980s, by the way.

Unfortunately, while China has one of the most developed programs of restricting religion and belief, it is far from alone.

The example of Hamza Kashgari, who was a Saudi blogger, shows how government policies in one place can cross borders. He tweeted some doubts about his faith, which is considered blasphemy. He fled to Australia to escape social cries for his beheading, only to be intercepted as he changed planes in Kuala Lumper, Malaysia, and extradited back to Saudi Arabia at the request of the Saudi government. After some jail time helped him overcome his doubts, he was released.

All this research has shown that restrictions on freedom of religion or belief coming from governments and groups in society reinforce each other and is a primary factor causing religions related violence.

All this research has shown that restrictions on freedom of religion or belief coming from governments and groups in society reinforce each other and is a primary factor causing religions related violence.

All of that is generally bad for business. Specifically, research I did while working with the World Economic Forum shows that high restrictions on freedom of religion or belief damage or even destroy the pillars of global competitiveness.

All of that is generally bad for business. Specifically, research I did while working with the World Economic Forum shows that high restrictions on freedom of religion or belief damage or even destroy the pillars of global competitiveness.

For example, as I mentioned a few minutes ago, innovative strength is more than twice as high in countries where governments respect freedom of religion or belief.

For example, as I mentioned a few minutes ago, innovative strength is more than twice as high in countries where governments respect freedom of religion or belief.

One indicator of that is whether some of a country’s top entrepreneurs and successful business people stay in a country or leave it.

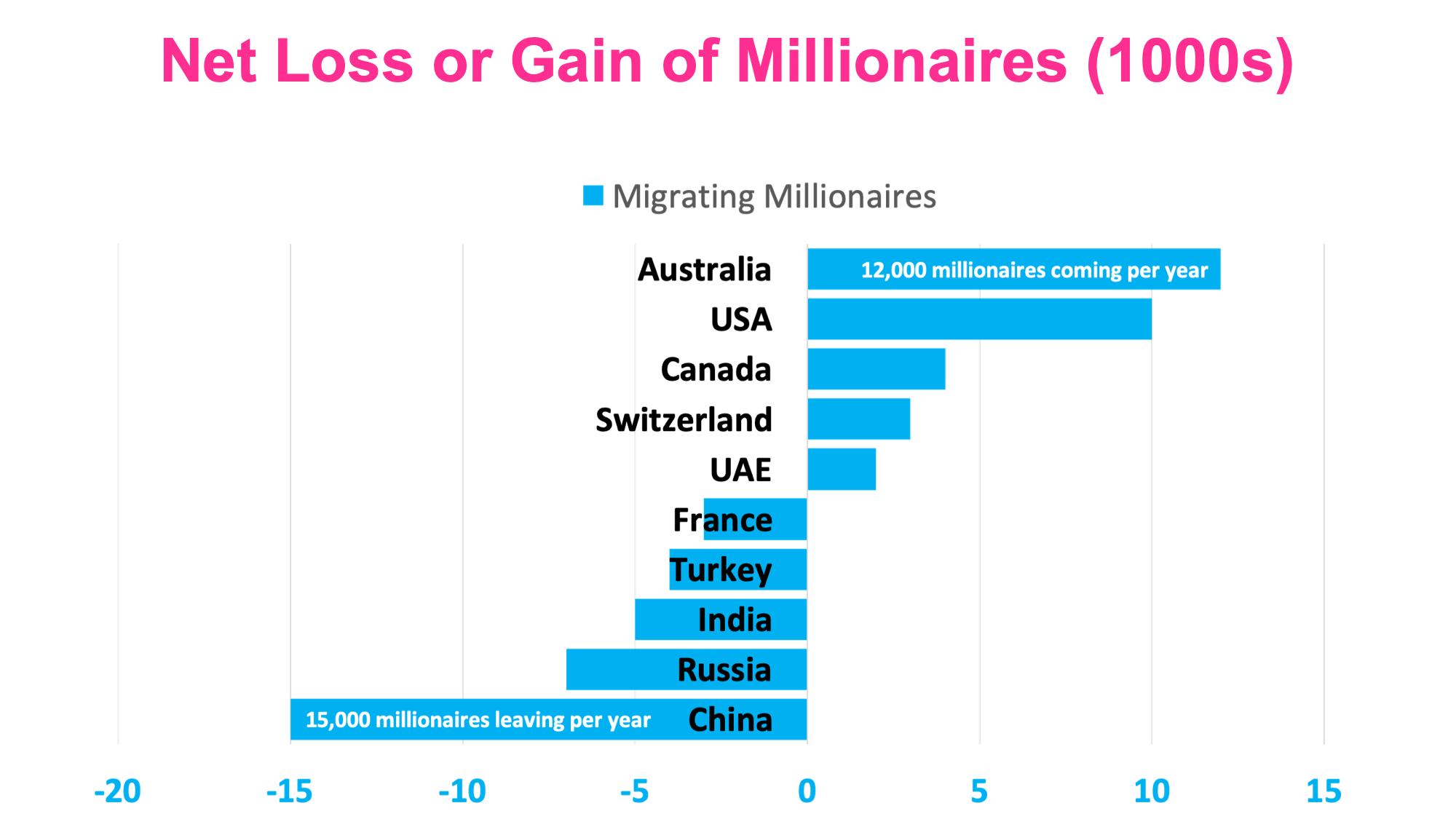

Bloomberg just published research showing which countries are losing or gaining millionaire through migration, with Australia gaining the most and China losing the most.

Bloomberg just published research showing which countries are losing or gaining millionaire through migration, with Australia gaining the most and China losing the most.

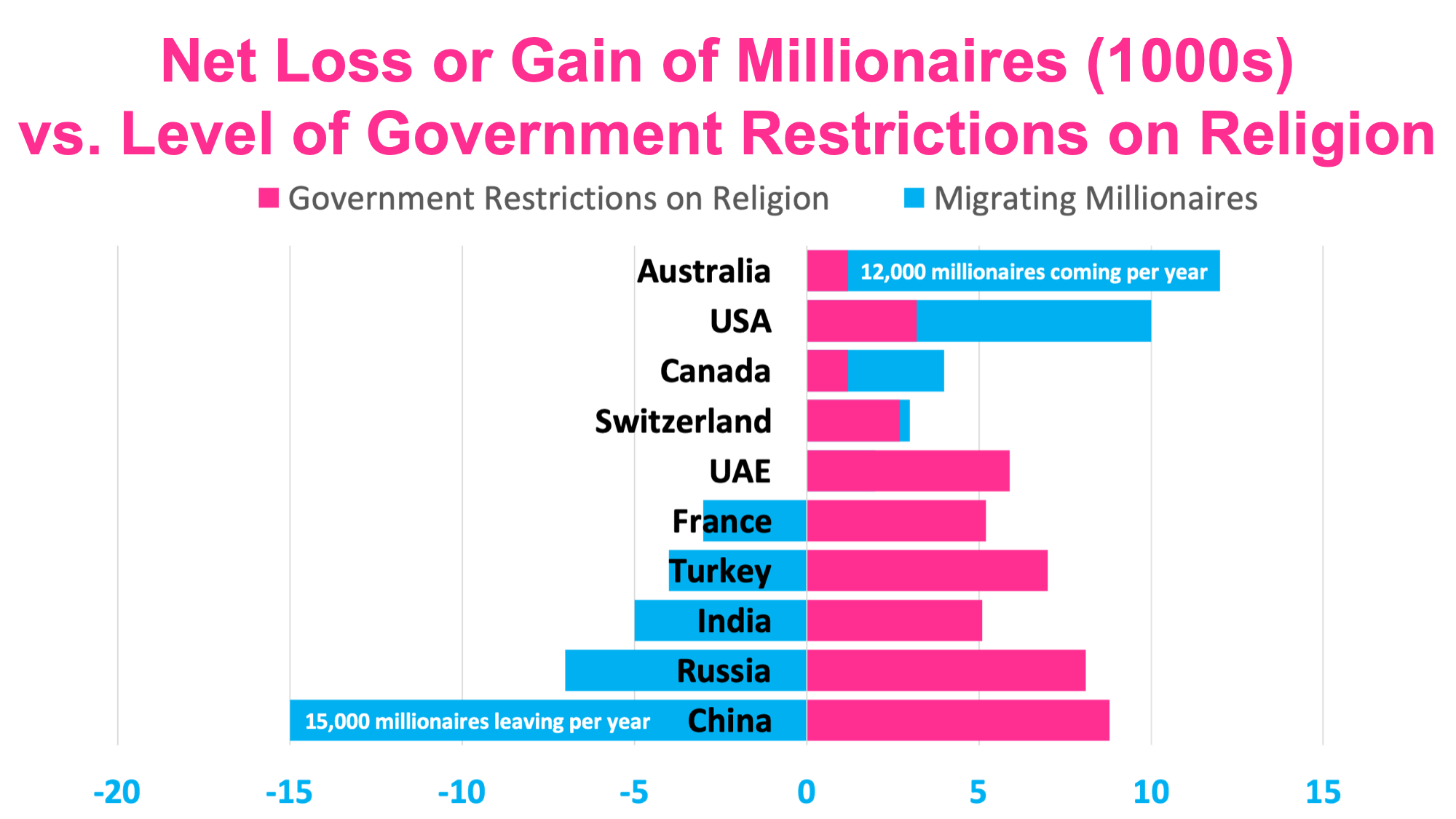

How does this compare with the level of government restrictions on religion and belief in a country?

As I mentioned, it’s not surprising that China, the country with the highest government restrictions on religion – as measured by the Pew Research Center – is also losing the highest number of millionaires seeking freer, more secure opportunities elsewhere. And Australia, a country with low government restrictions on religion, is benefiting the most from this migration of talent and resources. While the U.S. has relatively moderate government restrictions, it has high social hostilities, according to the past three annual reports by the Pew Research Center.

As I mentioned, it’s not surprising that China, the country with the highest government restrictions on religion – as measured by the Pew Research Center – is also losing the highest number of millionaires seeking freer, more secure opportunities elsewhere. And Australia, a country with low government restrictions on religion, is benefiting the most from this migration of talent and resources. While the U.S. has relatively moderate government restrictions, it has high social hostilities, according to the past three annual reports by the Pew Research Center.

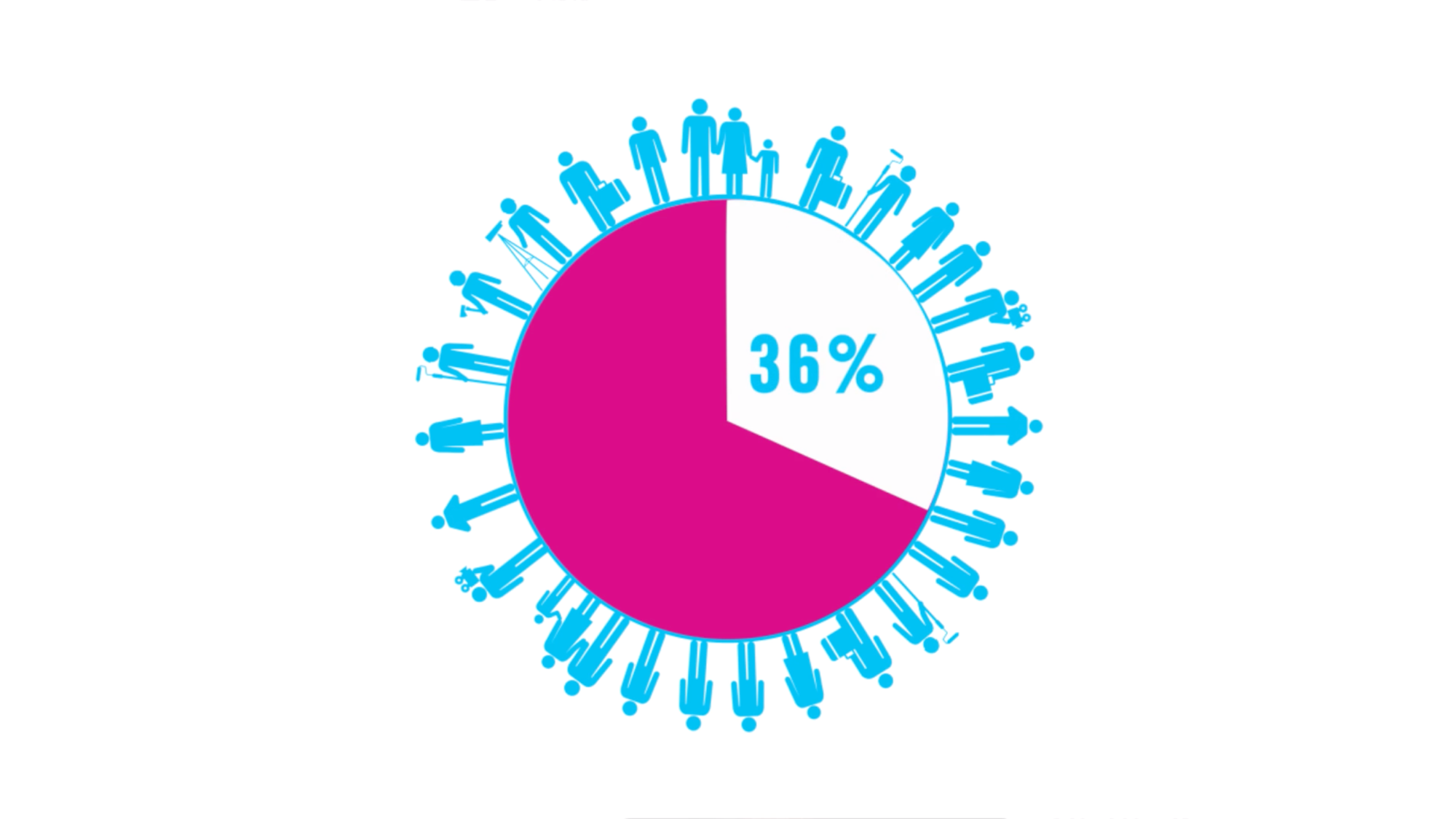

One place we see this is in the number of American workers who have experienced or witnessed religious discrimination in their workplace. A recent Tanenbaum survey finds that 36% of American workers, or about 50 million people, have experienced or witnessed some form of religious discrimination or non-accommodation in their workplace.

Despite this, religious diversity and inclusion is not on the minds of many companies.

Despite this, religious diversity and inclusion is not on the minds of many companies.

Companies have rightly paid a lot of attention to other diversity and inclusion issues, such as sexual orientation.

Now, religion is the next big thing businesses need to pay attention to.

In 2018, for instance, there were significantly more workplace discrimination complaints made to the EEOC over religion as complaints over sexual orientation.

The same business case that applies to other characteristics applies to including religion as part of diversity and inclusion initiatives.

The same business case that applies to other characteristics applies to including religion as part of diversity and inclusion initiatives.

So, what are some of the religious diversity and inclusion initiatives of major U.S. and international corporations? I’ll give just a few examples.

As we’ve heard today, this year Texas Instruments’ Diversity Network celebrates 30 years of diversity leadership and trailblazing.

TI was one of the early pioneers of instilling diversity into its corporate culture, embracing the premise that a diverse employee base is likely to facilitate fresh and valuable ideas; and that employees perform at higher levels when they’re permitted to “bring their whole selves to work”.

TI was one of the early pioneers of instilling diversity into its corporate culture, embracing the premise that a diverse employee base is likely to facilitate fresh and valuable ideas; and that employees perform at higher levels when they’re permitted to “bring their whole selves to work”.

Today the company has 15 grassroots, employee-led diversity resource groups (see image above) that help foster and support a diverse and inclusive work environment, including faith-oriented groups for Christian, Jewish and Muslim employees.

For the second year running, Bloomberg is hosting Tanenbaum’s Religious Diversity Leadership Summit, cosponsored by DTCC and the Walt Disney Company. The annual summit explores what’s next in addressing religious diversity & inclusion.

Accenture hosted a nation-wide webinar, “Religious Literacy 101 – What does it mean to have an accommodation mindset,” for Accenture employees on the case for being able to bring your whole self, faith and all, to work. Accenture has pioneered in both faith-specific and interfaith Employee Resource Groups.

Tyson Foods, along with many companies across the country, employs chaplains to minister to the needs of their multi-faith team members. Karen Diefendorf, a retire US Army Command Chaplain, leads their chaplain force. Here’s a short video of their work.

Worldwide, a number of companies adhere to a religious or belief-based ethos. For instance, Sanitarium, the most popular breakfast cereal company in Australia, is owned and operated by the Seventh Day Adventist Church. As a practical demonstration of the Church’s doctrinal dedication to health and well-being, Sanitarium is a South Pacific leader in producing healthy products and in organizing community programmes to encourage healthy lifestyles. One such Sanitarium programme is their popular nationwide TRYathlons, which inspire children to get moving in a friendly and supportive environment with an emphasis on enjoying the experience as part of an active lifestyle rather than competition. In fact, breakfast cereals in general have Adventist roots. The parent company of Sanitarium was Sanitas, the original company set up by then-Adventists John Harvey and W.K. Kellogg to manufacture toasted corn flakes as a healthier alternative to the greasy American breakfasts of the day. Yes, and now you know the religious roots of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes!

I’ll conclude with a call out to numerous companies that have signed the Corporate Pledge on Religious Diversity & Inclusion.

In the lunchtime session, we’ll specifically have an opportunity to explore and discuss resources aimed at helping companies fulfill the aspirations of the pledge, which you have a copy of on your chairs. This one minute video is a signing ceremony we held in Korea during the Paralympic Games when we give awards, in partnership with the United Nations Global Compact, for business leaders advancing interfaith understanding and peace.

In the lunchtime session, we’ll specifically have an opportunity to explore and discuss resources aimed at helping companies fulfill the aspirations of the pledge, which you have a copy of on your chairs. This one minute video is a signing ceremony we held in Korea during the Paralympic Games when we give awards, in partnership with the United Nations Global Compact, for business leaders advancing interfaith understanding and peace.