Religious Freedom and LGBT Rights

DOWNLOAD FULL STUDY: COMMON GROUND – LGBT Rights and Religious Freedom

Preface to the Study

The Religious Freedom & Business Foundation is a non-partisan NGO and does not take a position on current political debates. But we do conduct research that can inform policymakers and the public, including on issues that are hotly debated.

Unfortunately, “religious freedom” in the U.S. has become a divisive issue in recent years, mostly centered on issues related to sexuality and marriage. One side sees religious freedom as a protection against having to accommodate things they cannot conscientiously support, e.g., same-sex marriage. The other side sees that argument as discriminatory and a violation of civil rights law especially now that same-sex marriage is legal throughout the US.

As a social scientist studying the economic value of religious freedom worldwide (see my latest study), I took note of a recent study on the economic value of protecting the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people to live openly without discrimination and enjoy equal rights, personal autonomy, and freedom of expression and association. That raised a question: If both are positively correlated with global economic growth, what is their relationship to each other?

You will likely find the following results of the first study of its kind to be surprising. Given that extremely strong views exist on these issues, empirical data from a global perspective may point toward some common ground. Time will tell. But as the video above by RFBF Senior Corporate Advisor Kent Johnson shows, simultaneously protecting both religious and LGBT inclusion is entirely possible, as the example of Texas Instruments shows.

Brian Grim, Ph.D., RFBF President

Do Religious Freedom and LGBT Rights Have Common Ground?

Religious freedom – enshrined in the US Constitution’s first amendment – is central to our national identity. It is often called our first freedom because it constitutes the first two clauses of the US Bill of Rights: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Simple yet profound.

Religious freedom – enshrined in the US Constitution’s first amendment – is central to our national identity. It is often called our first freedom because it constitutes the first two clauses of the US Bill of Rights: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Simple yet profound.

Given our nation’s history, including the 1998 International Religious Freedom Act that passed the Senate unanimously during a time of extreme partisanship (President Clinton’s impeachment inquiry), some may be surprised to learn that the US does not rank highly on global measures of religious freedom.

According to the latest Pew Research Center data, there are 117 countries that place fewer restrictions on religion than the US.

In the US, restrictions on religion include laws and government policies such as prohibitions on proselytizing and controls on preaching (see Pew data). An earlier Pew report outlined other US government restrictions on religion, including such things as individuals being prevented from wearing certain religious attire or symbols; difficulties in obtaining zoning permits to build or expand houses of worship, religious schools or other religious institutions; and limits on conversion.

If we flip Pew’s data around, we can use lower restrictions on religion as a measure of religious freedom. It is not a perfect proxy because, for instance, the US prohibition of religious groups proselytizing while carrying out government-funded social service programs is widely accepted, and arguably protects religious freedom vis-à-vis preventing the establishment of a state favored religion. With this important caveat in mind, using low restrictions on religion as an indicator of religious freedom means that the US would rank 118th of 198 countries and territories in terms of religious freedom, as shown in the chart (see data used for this analysis here).

This illustrates that the state of religious freedom in the US is rightly a matter of national and international concern, and not just a concern for one political party or constituency. Unfortunately, “religious freedom” has domestically become a divisive issue in recent years, mostly centered on issues related to sexuality and marriage. One side sees religious freedom as a protection against having to accommodate things they cannot conscientiously support, e.g., same-sex marriage. The other side sees that argument as discriminatory and a violation of civil rights law especially now that same-sex marriage is legal throughout the US.

This ongoing debate has created a narrative, or at least perception, that religious freedom is incompatible with the growing public acceptance of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) people, lifestyles and rights, which the Pew Research Center has been tracking (see: 5 key findings about LGBT Americans and 5 facts about same-sex marriage).

Given that Pew studies show that religious freedom is deteriorating globally, it is important to understand the relationship religious freedom has with attitudes toward other emerging rights and issues.

Although domestically, proponents of LGBT rights and advocates for religious freedom have found themselves on opposite sides of debates, what does an analysis of global data on the intersection of religious freedom and LGBT rights reveal? If religious freedom and LGBT rights are in conflict globally, this would add another concern to an already concerning global situation.

DEFINITIONS UNDERLYING THE GLOBAL DATA

“Religious freedom” is defined as in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.”

“LGBT rights” are the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people to live openly without discrimination and enjoy equal rights, personal autonomy, and freedom of expression and association.

“Social hostilities involving religion” are hostile acts by private individuals, organizations and social groups that restrict religious beliefs and practices. These include mob or sectarian violence, crimes motivated by religious bias, physical conflict over conversions, harassment over attire for religious reasons, and other religion-related intimidation and violence, including terrorism and war.

DIGGING INTO THE DATA

To examine the intersection of religious freedom and LGBT rights, we can use the religious freedom measure calculated from the Pew data and compare it with public opinion data on LGBT people and LGBT rights from around the world put together by The Williams Institute, a UCLA Law School think tank (see data used in this analysis here) .

To examine the intersection of religious freedom and LGBT rights, we can use the religious freedom measure calculated from the Pew data and compare it with public opinion data on LGBT people and LGBT rights from around the world put together by The Williams Institute, a UCLA Law School think tank (see data used in this analysis here) .

The Williams Institute compiled major global surveys — such as Gallup and Pew Research Center polls — that contained questions to gauge public attitudes toward LGBT people and policies that guard them against discrimination. Using this information, they created the LGBT Global Acceptance Index (GAI), which provides scores for how much the publics in 141 countries of the world are supportive of LGBT people and of policies that protect their basic human rights.

Two initial notes: First, the United States ranks much better on the LGBT GAI index — 23rd — than it does on the religious freedom index (see chart). And second, about 6 in 10 LGBT people in the US are religiously affiliated, with the majority of the affiliated identifying with Christianity (see data).

5 QUESTIONS DATA CAN ANSWER

Now we can turn to 5 questions that data can answer.

Q1: First, do countries with higher levels of religious freedom have higher or lower levels of LGBT rights? Or put another way, does religious freedom foster a positive or negative environment for LGBT people?

A: Among the 137 countries that have both religious freedom and LGBT data, the average level of support for LGBT rights is 38% higher in countries with higher religious freedom than in countries with low levels of religious freedom. In the third of countries scoring the highest on religious freedom, the level of support for LGBT rights was 4.1 compared with only 2.9 in the third of countries scoring at the bottom of the scale on religious freedom (see chart).

Q2: Second, is support for LGBT rights increasing or decreasing in countries with higher levels of religious freedom?

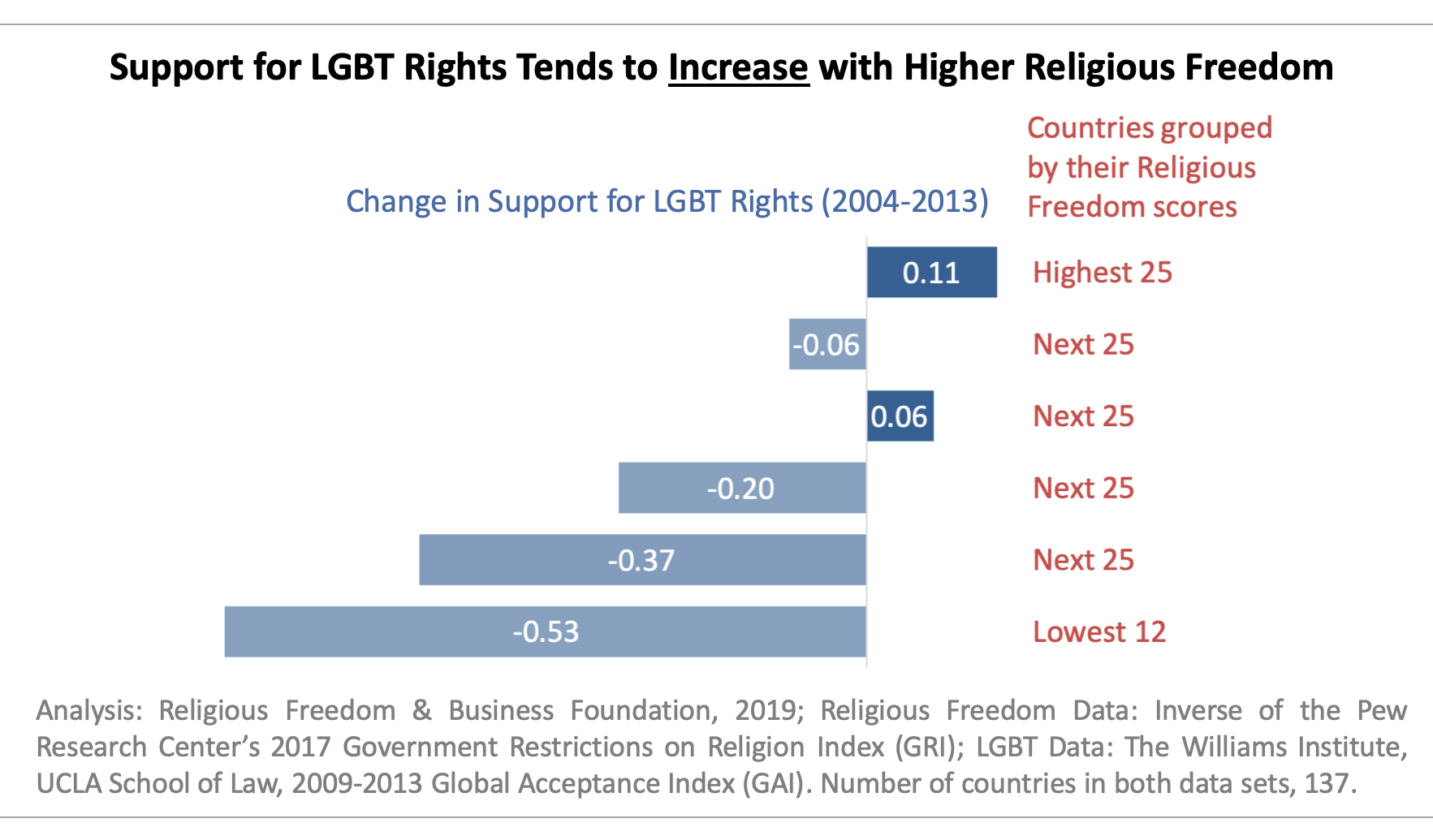

A: The level of support for LGBT rights is much more likely to be growing in religiously free countries than in religiously restricted countries, as seen in the chart below that looks at countries in groups of 25 (for demonstration purposes). Among the 25 countries with the highest levels of religious freedom, the LGBT GAI increased by 0.11 points between 2004-2013. By contrast, among the countries with the worst record on religious freedom (the lowest 12) the GAI decreased on average by 0.53 points, as shown in the chart. Also, if the lowest 25 are looked at, their average is -.047.

:

Example: Texas Instruments

In fact, among the 12 countries with the lowest levels of religious freedom, only one showed any improvement in support for LGBT rights, Vietnam. The remaining 11 countries all declined in support for LGBT rights between 2004-2013, as shown in the chart.

Q3: Third, is religious freedom higher or lower in countries where there is higher support for LGBT rights?

A: The average level of religious freedom is 36% higher in the countries with higher levels of support for LGBT rights than in countries with low levels of support for LGBT rights. In the one-third of countries scoring the highest on support for LGBT rights, the level of religious freedom was 7.5 compared with only 5.5 in the one-third of countries scoring at the bottom of the scale on support for LGBT rights (see chart).

The top five countries in support for LGBT rights all have religious freedom scores of 6.0 or higher: Iceland 6.3; Netherlands 7.4; Sweden 7.7; Denmark 6.0; and Andorra 7.6. The average level of religious freedom in these countries is 7.0, as shown in the chart.

It is important to point out that these associations are not a one-to-one correlation, but represent the general connections between religious freedom and support for LGBT rights. For example, as shown in the next chart, while the average level of religious freedom in the bottom five countries in LGBT acceptance is 3.8, or about half that of those with high support for LGBT rights, there is considerable variation in the scores of the bottom five countries: Egypt 2.0; Bangladesh 5.2; Saudi Arabia 2.2; Georgia 6.5; and Azerbaijan 3.2.

It is useful to note that support for LGBT rights in Georgia may be better than indicated by the LGBT Global Acceptance Index (GAI), which measures social attitudes rather than legal norms. According to the beta version of the Equaldex index on LGBT rights, Georgia scores much better than Russia, even though Russia (2.91) has a better score on the GAI than does Georgia (1.08).

Q4: Fourth, do countries with low levels of social hostilities involving religion have higher or lower support for LGBT rights?

A: On average, support for LGBT rights is 41% higher in countries with low levels of social hostilities involving religion. In the one-third of countries having the lowest levels of religious hostilities, the level of support for LGBT rights was 3.9 compared with only 2.8 in the one-third of countries scoring at the bottom of the religious hostilities scale (see chart; for more details on the concept of social hostilities involving religion, see Pew Research Center description of the SHI index).

This is of concern because for a number of years Pew Research data has placed the US in the “high” category of social hostilities involving religion (see data used for this analysis here).

Indeed, it is clear that social hostilities involving religion not only harm religious freedom but are a threat to all people. The recent spat of religiously biased violence in the US, including the 2018 Tree of Life Synagogue massacre in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, and the August 2019 alleged religiously and racially biased massacre in El Paso, Texas, are a shared threat to all.

Q5: And fifth, is religious freedom associated with higher or lower levels of social hostilities involving religion?

A: One of the clearest social science findings on religious freedom is its link to peace, non-violence and non-discrimination/non-persecution.

Together with coauthor Roger Finke, we detail the theory and science of religious freedom’s peace dividend in The Price of Freedom Denied (Cambridge Univ. Press). We show that, contrary to popular opinion, ensuring religious freedom for all reduces violent religious persecution and conflict. Others have suggested that restrictions on religion are necessary to maintain order or preserve a peaceful religious homogeneity. We show that restricting religious freedoms is associated with higher levels of violent persecution. Relying on data for nearly 200 countries and case studies of six countries, the book offers a global profile of religious freedom and religious persecution. While we report that persecution is evident in all regions and is standard fare for many, we also find that religious freedoms are routinely denied and that government and the society at large serve to restrict these freedoms. We conclude that the price of freedom denied is high indeed.

Together with coauthor Roger Finke, we detail the theory and science of religious freedom’s peace dividend in The Price of Freedom Denied (Cambridge Univ. Press). We show that, contrary to popular opinion, ensuring religious freedom for all reduces violent religious persecution and conflict. Others have suggested that restrictions on religion are necessary to maintain order or preserve a peaceful religious homogeneity. We show that restricting religious freedoms is associated with higher levels of violent persecution. Relying on data for nearly 200 countries and case studies of six countries, the book offers a global profile of religious freedom and religious persecution. While we report that persecution is evident in all regions and is standard fare for many, we also find that religious freedoms are routinely denied and that government and the society at large serve to restrict these freedoms. We conclude that the price of freedom denied is high indeed.

And to conclude on a hopeful note, while there are ongoing culture war debates over the extent and limits to religious freedom and LGBT rights in the US, various initiatives are seeking to set the battles to rest given that, as this report shows, the rights seem to rise and fall together. For example, see: Respectfully Sharing the Public Square: Protecting LGBT Rights and Religious Liberty.