Frank Fredericks | Founder & CEO of Mean Communications

Case Study Outline

- → Frank Fredericks Video (above)

- → Learning Objectives

- → Main Category of Action

- → Frank’s Story

- → Summary of Case

- → Interview withFrank Fredericks

- → Introduction to Global Restrictions on Religion

- – Religious Demographics

- – Conflict and Violence related to Religion

- → More About Frank Fredericks

- → Discussion Questions

- → Media and Added Resources

- → Role of Advertising

♦ Return to Templeton Religion Trust “Business Case Studies” Home

Learning Objectives

Frank Fredericks, Founder and CEO of Mean Communications, has created whole campaigns to combat stigmatization of “otherness.” He led his organization in a coalition with the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations, UNESCO, and other partners to produce a coordinated social media effort to spread awareness for the worldwide campaign “Do One Thing for Diversity and Inclusion.”

The learning objectives for this case study include:

- 1. Media can powerfully impact people’s perceptions of “otherness”.

- 2. Developing a communications strategy for a cause benefits from professional insights.

- 3. Many young people tend to focus on similarities between people more than differences, providing a hopeful avenue for advancing interfaith understanding and peace.

- 4. Interfaith action is more powerful than interfaith dialogue.

MAIN CATEGORY OF ACTION

Advocacy and public policy engagement

Fostering social cohesion and inter-group dialogue and relationship-building in the workplace, marketplace and local community.

Frank’s Story

Frank Fredericks says he does not believe in world peace — at least not the world peace many organizations aim for through talks, negotiations, meetings and more talks.

Fredericks believes in actions, not words; cooperation, not standoffs. That is the underlying principle at work at World Faith, the nonprofit organization he started in 2006 that brings young people of different faiths together to work on community projects in conflict zones.

“I founded World Faith out of the frustration that I don’t believe old people talking can counter young people taking action,” he said in a 2013 talk at American Middle Eastern Network for Dialogue at Stanford (AMENDS).

An evangelical Christian, Fredericks grew up in Clark County, Wash., a place he describes as lacking in diversity. “Our idea of religious diversity was having one Catholic church on one side of the county and a Mormon temple on the other,” he said in 2013.

He was still in high school during the 9/11 attacks and before that had given very little thought to people in other places with different ideas about faith. “That was a very quick jolt,” he said of the attacks. “I thought, what is it about my community that it fears people of other religions they have never met?”

While studying music at New York University, he traveled to Egypt to focus on Christian-Muslim relations. He met people from many different backgrounds there but was also shocked by the level of violence he saw and how quickly it could erupt. “All it would take was for someone to throw a rock through a mosque window and six people would be dead by morning,” he said.

On his return to New York, he founded World Faith. Today it operates in 11 countries and has brought together 3,000 individuals to perform 50,000 hours of community service.

“That is transformation,” he said. “And it doesn’t require us to come up with any peace solutions. It just requires us to humanize each other.”

Fredericks also founded Mean Communications, a digital consultancy that focuses on branding, social marketing, public relations and advertising for nonprofits, corporations and start-ups. His focus on humanizing “the other” — groups singled out in another group’s narrative, usually for blame or hatred — made him and Mean Communications a natural to work with the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations (UNAOC) and UNESCO to create the global “Do One Thing for Diversity and Inclusion” campaign, celebrated annually on May 21.

Like World Faith, “Do One Thing for Diversity and Inclusion” focuses on actions, not words, and on young people, not older ones. Participants were encouraged to do one of 10 “simple things” — learn about another religion, visit a museum exhibit about a different culture, cook food from a different part of the world, learn another language.

They were then encouraged to post a video of their experience on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram in an effort to globalize the effort and normalize “the other.”

Fredericks plans to expand Means Communications by partnering with other businesses to help them incorporate respect for diversity in their business practices. Respect for religious diversity is a good business practice, he said.

“Religious tolerance is not enough,” he said recently. “I tolerate back pain, I tolerate taxes. When it comes to promoting interfaith pluralism in a business environment, it helps us capture all the capacity people have to give. It is just in our best interest as a company to do so.”

Fredericks, who once knew little about diversity as a kid growing up in Washington state, now knows a lot more. He is married to a Muslim, Medina, and they life in Astoria, Queens, one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the most diverse city in the U.S.

“My faith informs my worldview,” he said in a speech in 2009. “That includes a belief that everyone should have a fair chance at success, that we should build more bridges than bombs, and that no interest should be a special interest.”

Summary of Case

Summary of Case

Many religious and cultural communities face “otherism” due to differences in education and underlying economic issues that often spur violence from perceived differences.

Frank Fredericks, Founder and CEO of Mean Communications, led his organization in a coalition with the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations, UNESCO, and other partners to produce a coordinated social media effort to spread awareness for the worldwide campaign “Do One Thing for Diversity and Inclusion.”

His efforts prompted individuals on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to participate in specific endeavors that support inclusion and cultural diversity and to show how their engagement in these actions helped overcome religious and cultural differences in their communities.

Interview with Frank Fredericks

Frank Fredericks on Good Morning America with Eboo Patel. Frank Fredericks and Soofia Ahmed from World Faith were on Good Morning America with Eboo Patel, who was sharing with Robin Roberts about the interfaith movement.

Introduction to Global Religion and Religious Restrictions

Religious Demographics (Pew Research Center)

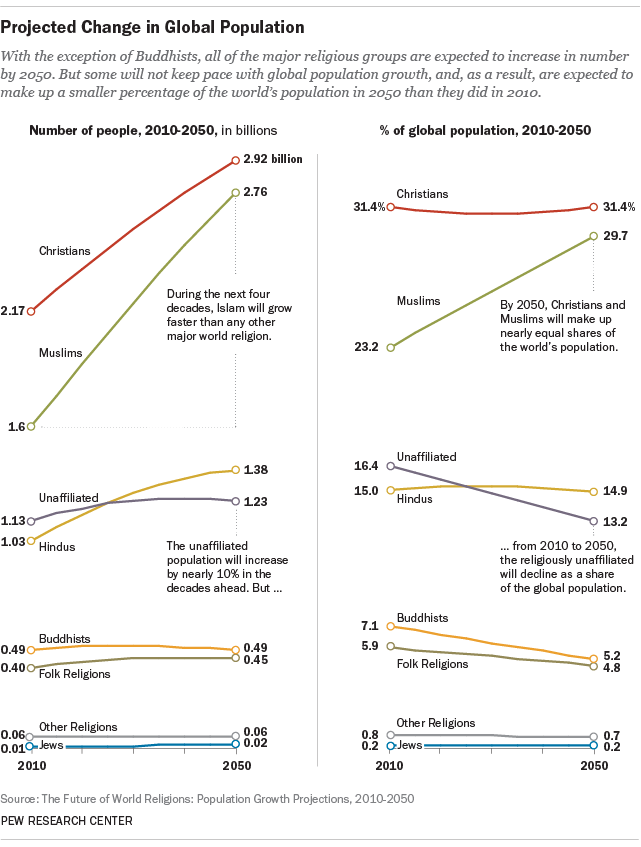

“The religious profile of the world is rapidly changing, driven primarily by differences in fertility rates and the size of youth populations among the world’s major religions, as well as by people switching faiths. Over the next four decades, Christians will remain the largest religious group, but Islam will grow faster than any other major religion. If current trends continue, by 2050 …

- – The number of Muslims will nearly equal the number of Christians around the world.

- – Atheists, agnostics and other people who do not affiliate with any religion – though increasing in countries such as the United States and France – will make up a declining share of the world’s total population.

- – The global Buddhist population will be about the same size it was in 2010, while the Hindu and Jewish populations will be larger than they are today.

- – In Europe, Muslims will make up 10% of the overall population.

- – India will retain a Hindu majority but also will have the largest Muslim population of any country in the world, surpassing Indonesia.

- – In the United States, Christians will decline from more than three-quarters of the population in 2010 to two-thirds in 2050, and Judaism will no longer be the largest non-Christian religion. Muslims will be more numerous in the U.S. than people who identify as Jewish on the basis of religion.

- – Four out of every 10 Christians in the world will live in sub-Saharan Africa.

These are among the global religious trends highlighted in new demographic projections by the Pew Research Center. The projections take into account the current size and geographic distribution of the world’s major religions, age differences, fertility and mortality rates, international migration and patterns in conversion.”

“As of 2010, Christianity was by far the world’s largest religion, with an estimated 2.2 billion adherents, nearly a third (31%) of all 6.9 billion people on Earth. Islam was second, with 1.6 billion adherents, or 23% of the global population.

If current demographic trends continue, however, Islam will nearly catch up by the middle of the 21st century. Between 2010 and 2050, the world’s total population is expected to rise to 9.3 billion, a 35% increase.1 Over that same period, Muslims – a comparatively youthful population with high fertility rates – are projected to increase by 73%. The number of Christians also is projected to rise, but more slowly, at about the same rate (35%) as the global population overall.

If current demographic trends continue, however, Islam will nearly catch up by the middle of the 21st century. Between 2010 and 2050, the world’s total population is expected to rise to 9.3 billion, a 35% increase.1 Over that same period, Muslims – a comparatively youthful population with high fertility rates – are projected to increase by 73%. The number of Christians also is projected to rise, but more slowly, at about the same rate (35%) as the global population overall.

As a result, according to the Pew Research projections, by 2050 there will be near parity between Muslims (2.8 billion, or 30% of the population) and Christians (2.9 billion, or 31%), possibly for the first time in history.2

With the exception of Buddhists, all of the world’s major religious groups are poised for at least some growth in absolute numbers in the coming decades. The global Buddhist population is expected to be fairly stable because of low fertility rates and aging populations in countries such as China, Thailand and Japan.

Worldwide, the Hindu population is projected to rise by 34%, from a little over 1 billion to nearly 1.4 billion, roughly keeping pace with overall population growth. Jews, the smallest religious group for which separate projections were made, are expected to grow 16%, from a little less than 14 million in 2010 to 16.1 million worldwide in 2050.”

Global Restrictions on Religion (Pew Research Center)

“For more than half a century, the United Nations and numerous international organizations have affirmed the principle of religious freedom.* For just as many decades, journalists and human rights groups have reported on persecution of minority faiths, outbreaks of sectarian violence and other pressures on religious individuals and communities in many countries. But until now, there has been no quantitative study that reviews an extensive number of sources to measure how governments and private actors infringe on religious beliefs and practices around the world.

Global Restrictions on Religion, a new study by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, finds that 64 nations – about one-third of the countries in the world – have high or very high restrictions on religion. But because some of the most restrictive countries are very populous, nearly 70 percent of the world’s 6.8 billion people live in countries with high restrictions on religion, the brunt of which often falls on religious minorities.

Some restrictions result from government actions, policies and laws. Others result from hostile acts by private individuals, organizations and social groups. The highest overall levels of restrictions are found in countries such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Iran, where both the government and society at large impose numerous limits on religious beliefs and practices. But government policies and social hostilities do not always move in tandem. Vietnam and China, for instance, have high government restrictions on religion but are in the moderate or low range when it comes to social hostilities. Nigeria and Bangladesh follow the opposite pattern: high in social hostilities but moderate in terms of government actions.

Among all regions, the Middle East-North Africa has the highest government and social restrictions on religion, while the Americas are the least restrictive region on both measures. Among the world’s 25 most populous countries , Iran, Egypt, Indonesia, Pakistan and India stand out as having the most restrictions when both measures are taken into account, while Brazil, Japan, the United States, Italy, South Africa and the United Kingdom have the least.

The Pew Forum’s study examines the incidence of many specific types of government and social restrictions on religion around the world. In 75 countries (38%), for example, national or local governments limit efforts by religious groups or individuals to persuade others to join their faith. In 178 countries (90%), religious groups must register with the government for various purposes, and in 117 (59%) the registration requirements resulted in major problems for, or outright discrimination against, certain faiths.

Public tensions between religious groups were reported in the vast majority (87%) of countries in the period studied (mid-2006 through mid-2008). In 126 countries (64%), these hostilities involved physical violence. In 49 countries (25%), private individuals or groups used force or the threat of force to compel adherence to religious norms. Religion-related terrorism caused casualties in 17 countries, nearly one-in-ten (9%) worldwide.

These are some of the key findings of Global Restrictions on Religion. The study covers 198 countries and self-administering territories, representing more than 99.5% of the world’s population. In preparing this study, the Pew Forum devised a battery of measures, phrased as questions, to gauge the levels of government and social restrictions on religion in each country. To answer these questions, Pew Forum researchers combed through 16 widely cited, publicly available sources of information, including reports by the U.S. State Department, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, the Council of the European Union, the United Kingdom’s Foreign & Commonwealth Office, Human Rights Watch, the International Crisis Group, the Hudson Institute and Amnesty International. (The complete list of sources is available in the Methodology.)

The researchers involved in this process recorded only factual reports about government actions, policies and laws, as well as specific incidents of religious violence or intolerance over the main two-year period covered by this study, from mid-2006 to mid-2008; they did not rely on the commentaries or opinions of the sources. (For a more detailed explanation of the coding and data verification procedures, see the Methodology. For the wording of the questions, see the Summary of Results.) The goal was to devise quantifiable, objective measures that could be combined into two comprehensive indexes, the Government Restrictions Index and the Social Hostilities Index. Using the current, two-year average as a baseline, future editions of the indexes will be able to chart changes and trends over time.

Global Restrictions on Religion is part of a larger effort – the Global Religious Futures Project, jointly funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation – that aims to increase knowledge and understanding of religion around the world.”

Religious Restrictions in the 25 Most Populous Countries

“This chart shows how the world’s 25 most populous countries score in terms of both government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. Countries in the upper right have the most restrictions and hostilities. Countries in the lower left have the least.”

Limitations of the Study

Limitations of the Study

“It is important to keep a few caveats in mind when reading this report. First, because freedom – defined as “the absence of hindrance, restraint, confinement or repression” – is difficult if not impossible to measure, the Pew Forum’s study instead measures the presence of restrictions of various kinds. The study tallies publicly reported incidents of religious violence, intolerance, intimidation and discrimination by governments and private actors. That is, it focuses on the problems in each country. It does not capture the other side of the coin: the amount of religious dynamism, diversity and expression in each country. The indexes of government restrictions and social hostilities are intended to measure obstacles to the practice of religion. But they are only part of a bigger picture.

Second, this study does not attach normative judgments to restrictions on religion. Every country studied has some restrictions on religion, and there may be strong public support in particular countries for laws aimed, for example, at curbing “cult” activity (as in France), preserving an established church (as in the United Kingdom) or keeping tax-exempt religious organizations from endorsing candidates for elected office (as in the United States). The study does not attempt to determine whether particular restrictions are justified or unjustified. Nor does it attempt to analyze the many factors – historical, demographic, cultural, religious, economic and political – that might explain why restrictions have arisen. It seeks simply to measure the restrictions that exist in a quantifiable, transparent and reproducible way, based on reports from numerous governmental and nongovernmental organizations.

Finally, although it is very likely that more restrictions exist than are reported by the 16 primary sources, taken together the sources are sufficiently comprehensive to provide a good estimate of the levels of restrictions in almost all countries. The one major exception is North Korea. The sources clearly indicate that North Korea’s government is among the most repressive in the world with respect to religion as well as other civil and political liberties. (The U.S. State Department’s 2008 Report on International Religious Freedom, for example, says that “Genuine freedom of religion does not exist” in North Korea.) But because North Korean society is effectively closed to outsiders and independent observers lack regular access to the country, the sources are unable to provide the kind of specific, timely information that the Pew Forum categorized and counted (“coded,” in social science parlance) for this quantitative study. Therefore, the report does not include scores for North Korea.”

Footnote

* According to Article 18 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, one of the foundational documents of the U.N., “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.” (back to top)

More About Frank Fredricks

“It was my final semester at New York University, and I had it all figured out. Sure, I had my finals, and picking up my cap and gown, but I knew I was going to graduate and begin immediately working full-time leading World Faith, an interfaith youth action organization I founded the year before. This was a pretty significant departure from my original plan. I was graduating from the Music Business program at NYU, and had already founded my own record label, Çöñàr Records, as well as producing records, booking shows, and managing artists such as Lady Gaga, Childish Gambino, Honey Larochelle, and Elin.

After spending months building World Faith Chapters from Lebanon to Sudan, I returned to the US with the realization that I wouldn’t be able to raise enough funding to cover my own salary. So I spent a full day preparing an updated resume, cover letter, and went to bed with the plan to begin applying the next morning. The next morning on Sept 29, after scanning job postings, I opened the Huffington Post to find the headline “Dow Jones Drops 777 points.” Suddenly the job postings vanished, and like many young people, I was running out of options.

One of the main skills I gained from my work in the music industry was that of social media and marketing. So, with little prospects of getting a “real job,” I began freelancing in social media to make enough money, while saving enough time to run World Faith. My first gig was a web design project for a Jamaican tour guide, named Sexy Rexy. What began as a short contract turned into a two year journey, in which we built a full social media presence, a video campaign with over a million views, and a short documentary on the hysterically complicated character of Sexy Rexy, complete with taking a film crew to Jamaica twice. It was a curious amazing experience, particularly for a former music manager turned social entrepreneur.

Between leading World Faith into spreading across a dozen countries spanning the globe, and my unique film project, I began getting referrals for more consulting work. One day, Samir Selmanovic, who I like to call the interfaith Einstein, brought me to meet a couple who run connected interfaith organizations, who were concerned about promoting their joint new project. Progressive Muslims themselves, they were looking to get the message about a new community center they wanted to build a few blocks from the mosque the husband of the couple led. After signing a three-month contract to help them with social media and PR, I got straight to work. Scanning blogs, I noticed that a blogger from the Bronx wrote a scathing dissent of the project, dubbing it “the Ground Zero Mosque.” In what could only be called the Summer of Islamophobia, I witnessed the unjust characterization of good people as extremists from the inside while consulting them during those months. Once I finished the contract, I partnered with my good friend Joshua Stanton to foundReligious Freedom USA. We began advocating for Jewish and Christian leaders to speak out in support of Park51, and organized a 1,000-person demonstration called the Liberty Walk.

Over the past few years, World Faith has grown into one of the largest interfaith development organizations in world. In 2012, we mobilized over 3,000 volunteers to complete of 50,000 hours of service. At the same time, my freelance consulting has grown, completely by word of mouth, until it become time to grow up, build a brand, and hire some brilliant folks to join me. Michelle is a recent graduate of Dartmouth, with an obsession for web platforms (and science fiction). Rico is a much sought-after designer, who just happens to be a world-class poet on the side.”

Discussion Questions

- 1. Identify other examples of how media can powerfully impact people’s perceptions of “otherness”.

- 2. In what ways can a communications strategy for a cause benefit from professional insights?

- 3. Why do some but not all young people focus on similarities between people more than differences?

- 4. In what ways is interfaith action more powerful than interfaith dialogue?

Media and Added Resources

World Economic Forum 2016: How are ancient religions adapting and evolving in 21st century societies?

- – UNAOC Do One Thing page

- – FaceBook Do One Thing page

Role of Advertising

- – Coke Serves Up Love and Peace with Small World Machines

- – Amazon Bridges Difference Through a Shared Problem

This case study was prepared by Melissa Grim, J.D., M.T.S., a senior research fellow with the Religious Freedom & Business Foundation, and Brian Grim, Ph.D., president of the foundation. It is made possible by a generous grant from the Templeton Religion Trust.