By Brian J. Grim, Ph.D.

By Brian J. Grim, Ph.D.

At the 2020 Faith@Work interfaith conference at the Catholic University of America’s Busch School of Business in Washington DC, the school’s dean, Andrew Abela, delivered a keynote calling for virtuous business. In an age when declining trust in public institutions is rising, it is not surprising that behind that trend is a diminishing supply of virtue.

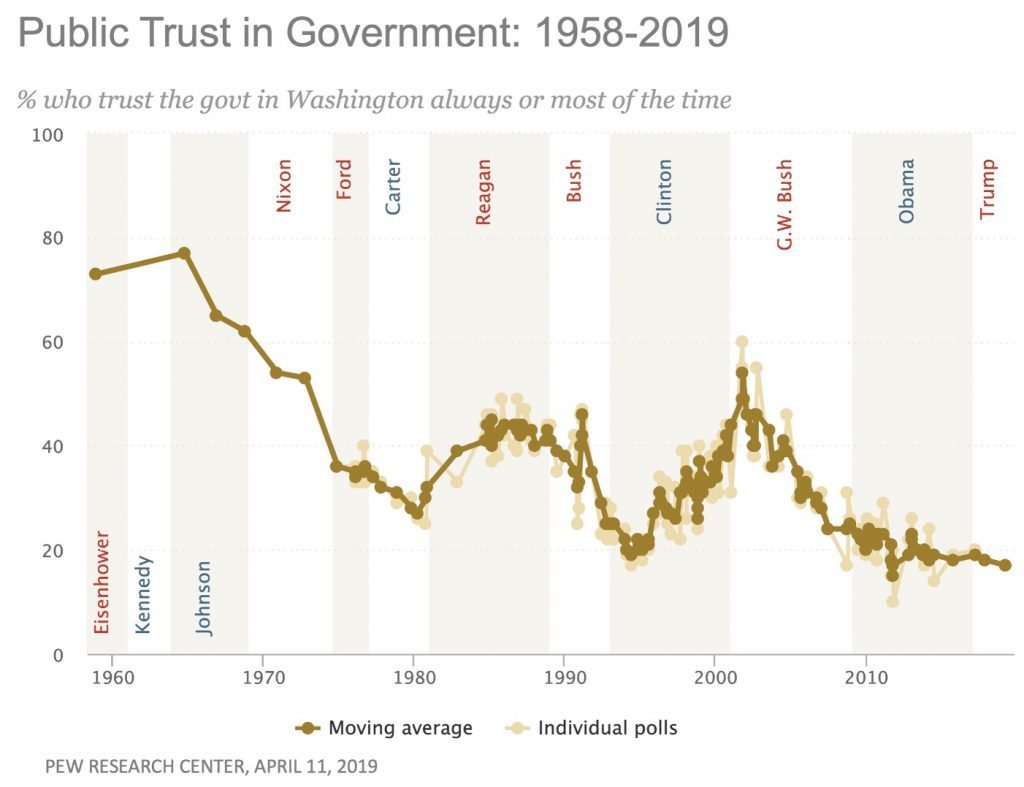

Indeed, trust is in short supply. Globally, the Edelman Trust Barometer’s 2020 report shows especially low confidence in government and media, with business and NGOs also losing ground. And in the United States, this trend didn’t just develop during the current administration, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center study; the decline in trust has been trending since 1958 (see chart).

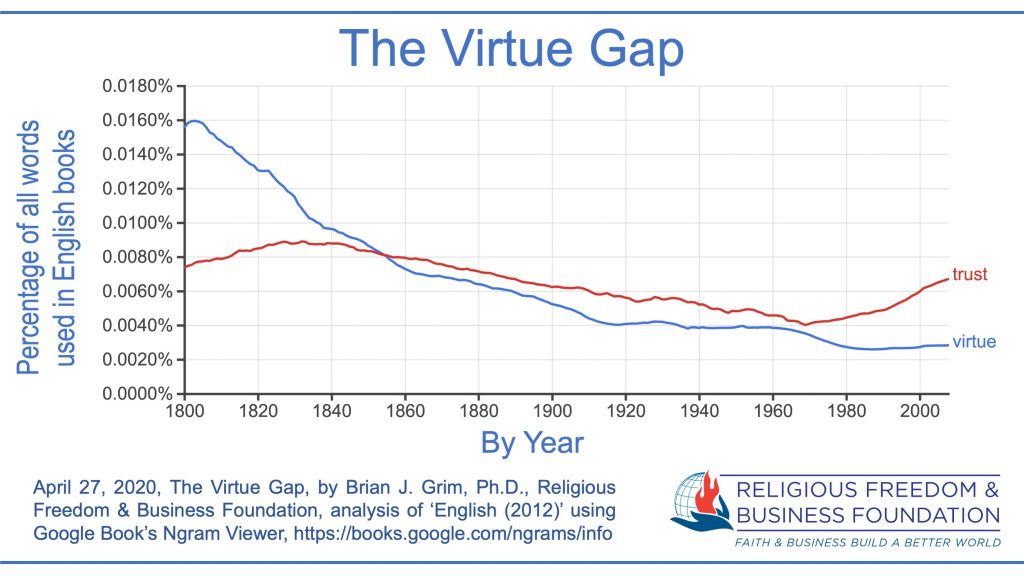

My hypothesis is that the decline in trust and the rise in calls for corporate social responsibility are related to the decline in the practice of virtue. One snapshot of this is an analysis of how often ‘virtue’ appears in books over the past two centuries. The analysis, shown in the chart below, finds that virtue had its heyday about 220 years ago with a somewhat steady decline in usage up to the present (assuming that talking about virtue is a rough indication of its social currency).

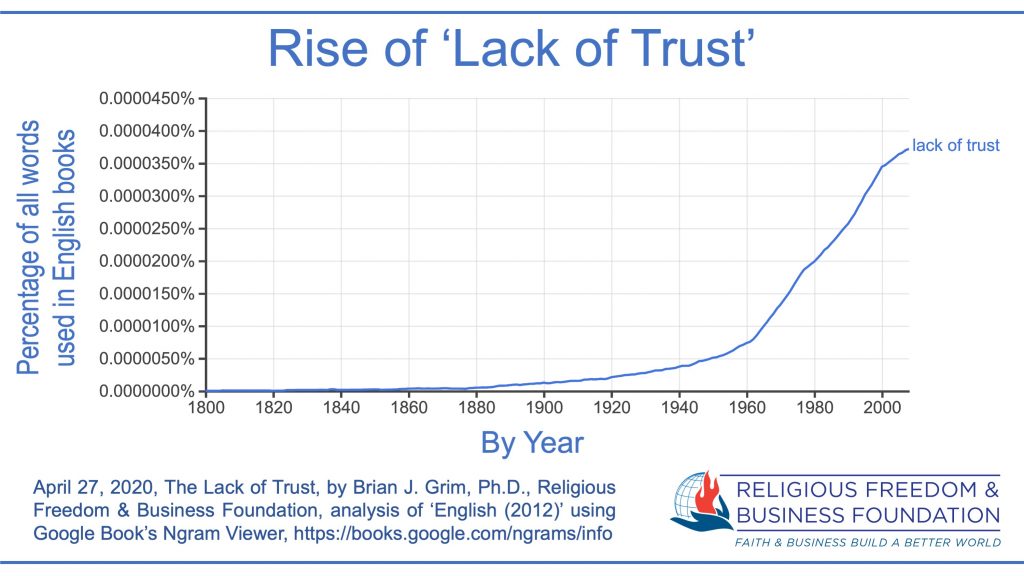

The decline in talk of virtue is matched in the rise of talk of trust, i.e., more often the lack of trust (see chart). The gap between virtue and trust shown by the chart above is just one indicator of the problem and of a potential solution — the return of virtue to business (and government, media and NGOs).

Now, back to Dean Abela’s proposition that virtue in business holds solutions. He begins by quoting the Second Vatican Council, which declared that “the split between the faith which many profess and their daily lives deserves to be counted among the more serious errors of our age.” He dispels the notion that just because someone is religious, on Sunday for instance, that that makes them virtuous the rest of the week.

For example, Abela cites a study of more than 200 in-depth interviews of highly religious IT managers. The study by sociologist Brandon Vaidyanathan, and summarized in his book Mercenaries and Missionaries, found that an “apprehensive individualism” generated in global corporate workplaces is supported and sustained by a “therapeutic individualism” cultivated in evangelical-charismatic Catholicism. They applied their spirituality to their own motivation and meaning in life, but largely didn’t connect that to their work, where they reported saying such things as: “I’m just in it for the cash,” or “I don’t care anything about loyalty to the company,” or “You may need to agree with what they ask you but you just need to do it to get the promotion.”

This study shines a light on the split the Vatican Council decried decades earlier. Abela notes that one of the reasons for this incongruity is the implicit assumption that being effective at work and being religious are “at best irrelevant to each other or at worst incompatible.” The challenge is how to bring those two worlds completely and fully together — to live a unified life, an integrated life, a life of integrity.

At the Busch School, Abela offers, they have a useful way of teaching their business students how to overcome the divide by applying the concepts of virtue. Virtues are simply good habits. And the opposite of a virtue is a vice, a bad habit.

At the Busch School, Abela offers, they have a useful way of teaching their business students how to overcome the divide by applying the concepts of virtue. Virtues are simply good habits. And the opposite of a virtue is a vice, a bad habit.

The great thing about virtues – good habits — is that they can be practiced and anybody can grow in virtue, says Abela. And as this makes for better people, better relationships, better communities, and better business through their practice.

The four cardinal virtues are prudence (habit of making wise decisions), justice (habit of being fair to others), fortitude or courage (habit of doing the right thing even when you’re afraid), and temperance (habit of resisting the temptation to do something wrong).

Abela proposes that practicing the virtues is a way for religious people to live out their faith at work. And the beauty of it is that the virtues can be practiced by anyone, religious or not. In fact, the four cardinal virtues didn’t come out of religion, but philosophy, Plato.

Circling back to my hypothesis that the decline in trust and the rise in calls for corporate social responsibility are related to a decline in the practice of virtue. We now have the opportunity and practical tools to address the lack of trust in our societies, first, by taking up the challenge to practice the virtues in our own lives. And second, by exercising leadership and promoting the practice of these virtues in our spheres of influence (family, workplace, business, public life, etc.).

Of course, this is much broader than a business school curriculum. It is a paradigm shift toward virtue at home, school, work, public life, and within religions themselves.